VOLUME FOUR

Chapter 74. The Villefort Family Vault

Two days after, a considerable crowd was assembled, towards ten o’clock in the morning, around the door of M. de Villefort’s house, and a long file of mourning-coaches and private carriages extended along the Faubourg Saint-Honoré and the Rue de la Pépinière. Among them was one of a very singular form, which appeared to have come from a distance. It was a kind of covered wagon, painted black, and was one of the first to arrive. Inquiry was made, and it was ascertained that, by a strange coincidence, this carriage contained the corpse of the Marquis de Saint-Méran, and that those who had come thinking to attend one funeral would follow two. Their number was great. The Marquis de Saint-Méran, one of the most zealous and faithful dignitaries of Louis XVIII. and King Charles X., had preserved a great number of friends, and these, added to the personages whom the usages of society gave Villefort a claim on, formed a considerable body.

Due information was given to the authorities, and permission obtained that the two funerals should take place at the same time. A second hearse, decked with the same funereal pomp, was brought to M. de Villefort’s door, and the coffin removed into it from the post-wagon. The two bodies were to be interred in the cemetery of Père-Lachaise, where M. de Villefort had long since had a tomb prepared for the reception of his family. The remains of poor Renée were already deposited there, and now, after ten years of separation, her father and mother were to be reunited with her.

The Parisians, always curious, always affected by funereal display, looked on with religious silence while the splendid procession accompanied to their last abode two of the number of the old aristocracy—the greatest protectors of commerce and sincere devotees to their principles.

In one of the mourning-coaches Beauchamp, Debray, and Château-Renaud were talking of the very sudden death of the marchioness.

“I saw Madame de Saint-Méran only last year at Marseilles, when I was coming back from Algiers,” said Château-Renaud; “she looked like a woman destined to live to be a hundred years old, from her apparent sound health and great activity of mind and body. How old was she?”

“Franz assured me,” replied Albert, “that she was sixty-six years old. But she has not died of old age, but of grief; it appears that since the death of the marquis, which affected her very deeply, she has not completely recovered her reason.”

“But of what disease, then, did she die?” asked Debray.

“It is said to have been a congestion of the brain, or apoplexy, which is the same thing, is it not?”

“Nearly.”

“It is difficult to believe that it was apoplexy,” said Beauchamp. “Madame de Saint-Méran, whom I once saw, was short, of slender form, and of a much more nervous than sanguine temperament; grief could hardly produce apoplexy in such a constitution as that of Madame de Saint-Méran.”

“At any rate,” said Albert, “whatever disease or doctor may have killed her, M. de Villefort, or rather, Mademoiselle Valentine,—or, still rather, our friend Franz, inherits a magnificent fortune, amounting, I believe, to 80,000 livres per annum.”

“And this fortune will be doubled at the death of the old Jacobin, Noirtier.”

“That is a tenacious old grandfather,” said Beauchamp. “Tenacem propositi virum. I think he must have made an agreement with death to outlive all his heirs, and he appears likely to succeed. He resembles the old Conventionalist of ’93, who said to Napoleon, in 1814, ‘You bend because your empire is a young stem, weakened by rapid growth. Take the Republic for a tutor; let us return with renewed strength to the battle-field, and I promise you 500,000 soldiers, another Marengo, and a second Austerlitz. Ideas do not become extinct, sire; they slumber sometimes, but only revive the stronger before they sleep entirely.’”

“Ideas and men appeared the same to him,” said Albert. “One thing only puzzles me, namely, how Franz d’Épinay will like a grandfather who cannot be separated from his wife. But where is Franz?”

“In the first carriage, with M. de Villefort, who considers him already as one of the family.”

Such was the conversation in almost all the carriages; these two sudden deaths, so quickly following each other, astonished everyone, but no one suspected the terrible secret which M. d’Avrigny had communicated, in his nocturnal walk to M. de Villefort. They arrived in about an hour at the cemetery; the weather was mild, but dull, and in harmony with the funeral ceremony. Among the groups which flocked towards the family vault, Château-Renaud recognized Morrel, who had come alone in a cabriolet, and walked silently along the path bordered with yew-trees.

“You here?” said Château-Renaud, passing his arms through the young captain’s; “are you a friend of Villefort’s? How is it that I have never met you at his house?”

“I am no acquaintance of M. de Villefort’s,” answered Morrel, “but I was of Madame de Saint-Méran.” Albert came up to them at this moment with Franz.

“The time and place are but ill-suited for an introduction.” said Albert; “but we are not superstitious. M. Morrel, allow me to present to you M. Franz d’Épinay, a delightful travelling companion, with whom I made the tour of Italy. My dear Franz, M. Maximilian Morrel, an excellent friend I have acquired in your absence, and whose name you will hear me mention every time I make any allusion to affection, wit, or amiability.”

Morrel hesitated for a moment; he feared it would be hypocritical to accost in a friendly manner the man whom he was tacitly opposing, but his oath and the gravity of the circumstances recurred to his memory; he struggled to conceal his emotion and bowed to Franz.

“Mademoiselle de Villefort is in deep sorrow, is she not?” said Debray to Franz.

“Extremely,” replied he; “she looked so pale this morning, I scarcely knew her.”

These apparently simple words pierced Morrel to the heart. This man had seen Valentine, and spoken to her! The young and high-spirited officer required all his strength of mind to resist breaking his oath. He took the arm of Château-Renaud, and turned towards the vault, where the attendants had already placed the two coffins.

“This is a magnificent habitation,” said Beauchamp, looking towards the mausoleum; “a summer and winter palace. You will, in turn, enter it, my dear d’Épinay, for you will soon be numbered as one of the family. I, as a philosopher, should like a little country-house, a cottage down there under the trees, without so many free-stones over my poor body. In dying, I will say to those around me what Voltaire wrote to Piron: ‘Eo rus, and all will be over.’ But come, Franz, take courage, your wife is an heiress.”

“Indeed, Beauchamp, you are unbearable. Politics has made you laugh at everything, and political men have made you disbelieve everything. But when you have the honor of associating with ordinary men, and the pleasure of leaving politics for a moment, try to find your affectionate heart, which you leave with your stick when you go to the Chamber.”

“But tell me,” said Beauchamp, “what is life? Is it not a halt in Death’s anteroom?”

“I am prejudiced against Beauchamp,” said Albert, drawing Franz away, and leaving the former to finish his philosophical dissertation with Debray.

The Villefort vault formed a square of white stones, about twenty feet high; an interior partition separated the two families, and each apartment had its entrance door. Here were not, as in other tombs, ignoble drawers, one above another, where thrift bestows its dead and labels them like specimens in a museum; all that was visible within the bronze gates was a gloomy-looking room, separated by a wall from the vault itself. The two doors before mentioned were in the middle of this wall, and enclosed the Villefort and Saint-Méran coffins. There grief might freely expend itself without being disturbed by the trifling loungers who came from a picnic party to visit Père-Lachaise, or by lovers who make it their rendezvous.

The two coffins were placed on trestles previously prepared for their reception in the right-hand crypt belonging to the Saint-Méran family. Villefort, Franz, and a few near relatives alone entered the sanctuary.

As the religious ceremonies had all been performed at the door, and there was no address given, the party all separated; Château-Renaud, Albert, and Morrel, went one way, and Debray and Beauchamp the other. Franz remained with M. de Villefort; at the gate of the cemetery Morrel made an excuse to wait; he saw Franz and M. de Villefort get into the same mourning-coach, and thought this meeting forboded evil. He then returned to Paris, and although in the same carriage with Château-Renaud and Albert, he did not hear one word of their conversation.

As Franz was about to take leave of M. de Villefort, “When shall I see you again?” said the latter.

“At what time you please, sir,” replied Franz.

“As soon as possible.”

“I am at your command, sir; shall we return together?”

“If not unpleasant to you.”

“On the contrary, I shall feel much pleasure.”

Thus, the future father and son-in-law stepped into the same carriage, and Morrel, seeing them pass, became uneasy. Villefort and Franz returned to the Faubourg Saint-Honoré. The procureur, without going to see either his wife or his daughter, went at once to his study, and, offering the young man a chair:

“M. d’Épinay,” said he, “allow me to remind you at this moment,—which is perhaps not so ill-chosen as at first sight may appear, for obedience to the wishes of the departed is the first offering which should be made at their tomb,—allow me then to remind you of the wish expressed by Madame de Saint-Méran on her death-bed, that Valentine’s wedding might not be deferred. You know the affairs of the deceased are in perfect order, and her will bequeaths to Valentine the entire property of the Saint-Méran family; the notary showed me the documents yesterday, which will enable us to draw up the contract immediately. You may call on the notary, M. Deschamps, Place Beauveau, Faubourg Saint-Honoré, and you have my authority to inspect those deeds.”

“Sir,” replied M. d’Épinay, “it is not, perhaps, the moment for Mademoiselle Valentine, who is in deep distress, to think of a husband; indeed, I fear——”

“Valentine will have no greater pleasure than that of fulfilling her grandmother’s last injunctions; there will be no obstacle from that quarter, I assure you.”

“In that case,” replied Franz, “as I shall raise none, you may make arrangements when you please; I have pledged my word, and shall feel pleasure and happiness in adhering to it.”

“Then,” said Villefort, “nothing further is required. The contract was to have been signed three days since; we shall find it all ready, and can sign it today.”

“But the mourning?” said Franz, hesitating.

“Don’t be uneasy on that score,” replied Villefort; “no ceremony will be neglected in my house. Mademoiselle de Villefort may retire during the prescribed three months to her estate of Saint-Méran; I say hers, for she inherits it today. There, after a few days, if you like, the civil marriage shall be celebrated without pomp or ceremony. Madame de Saint-Méran wished her daughter should be married there. When that is over, you, sir, can return to Paris, while your wife passes the time of her mourning with her mother-in-law.”

“As you please, sir,” said Franz.

“Then,” replied M. de Villefort, “have the kindness to wait half an hour; Valentine shall come down into the drawing-room. I will send for M. Deschamps; we will read and sign the contract before we separate, and this evening Madame de Villefort shall accompany Valentine to her estate, where we will rejoin them in a week.”

“Sir,” said Franz, “I have one request to make.”

“What is it?”

“I wish Albert de Morcerf and Raoul de Château-Renaud to be present at this signature; you know they are my witnesses.”

“Half an hour will suffice to apprise them; will you go for them yourself, or shall you send?”

“I prefer going, sir.”

“I shall expect you, then, in half an hour, baron, and Valentine will be ready.”

Franz bowed and left the room. Scarcely had the door closed, when M. de Villefort sent to tell Valentine to be ready in the drawing-room in half an hour, as he expected the notary and M. d’Épinay and his witnesses. The news caused a great sensation throughout the house; Madame de Villefort would not believe it, and Valentine was thunderstruck. She looked around for help, and would have gone down to her grandfather’s room, but on the stairs she met M. de Villefort, who took her arm and led her into the drawing-room. In the anteroom, Valentine met Barrois, and looked despairingly at the old servant. A moment later, Madame de Villefort entered the drawing-room with her little Edward. It was evident that she had shared the grief of the family, for she was pale and looked fatigued. She sat down, took Edward on her knees, and from time to time pressed this child, on whom her affections appeared centred, almost convulsively to her bosom.

Two carriages were soon heard to enter the courtyard. One was the notary’s; the other, that of Franz and his friends. In a moment the whole party was assembled. Valentine was so pale one might trace the blue veins from her temples, round her eyes and down her cheeks. Franz was deeply affected. Château-Renaud and Albert looked at each other with amazement; the ceremony which was just concluded had not appeared more sorrowful than did that which was about to begin. Madame de Villefort had placed herself in the shadow behind a velvet curtain, and as she constantly bent over her child, it was difficult to read the expression of her face. M. de Villefort was, as usual, unmoved.

The notary, after having, according to the customary method, arranged the papers on the table, taken his place in an armchair, and raised his spectacles, turned towards Franz:

“Are you M. Franz de Quesnel, baron d’Épinay?” asked he, although he knew it perfectly.

“Yes, sir,” replied Franz. The notary bowed.

“I have, then, to inform you, sir, at the request of M. de Villefort, that your projected marriage with Mademoiselle de Villefort has changed the feeling of M. Noirtier towards his grandchild, and that he disinherits her entirely of the fortune he would have left her. Let me hasten to add,” continued he, “that the testator, having only the right to alienate a part of his fortune, and having alienated it all, the will will not bear scrutiny, and is declared null and void.”

“Yes.” said Villefort; “but I warn M. d’Épinay, that during my life-time my father’s will shall never be questioned, my position forbidding any doubt to be entertained.”

“Sir,” said Franz, “I regret much that such a question has been raised in the presence of Mademoiselle Valentine; I have never inquired the amount of her fortune, which, however limited it may be, exceeds mine. My family has sought consideration in this alliance with M. de Villefort; all I seek is happiness.”

Valentine imperceptibly thanked him, while two silent tears rolled down her cheeks.

“Besides, sir,” said Villefort, addressing himself to his future son-in-law, “excepting the loss of a portion of your hopes, this unexpected will need not personally wound you; M. Noirtier’s weakness of mind sufficiently explains it. It is not because Mademoiselle Valentine is going to marry you that he is angry, but because she will marry, a union with any other would have caused him the same sorrow. Old age is selfish, sir, and Mademoiselle de Villefort has been a faithful companion to M. Noirtier, which she cannot be when she becomes the Baroness d’Épinay. My father’s melancholy state prevents our speaking to him on any subjects, which the weakness of his mind would incapacitate him from understanding, and I am perfectly convinced that at the present time, although, he knows that his granddaughter is going to be married, M. Noirtier has even forgotten the name of his intended grandson.” M. de Villefort had scarcely said this, when the door opened, and Barrois appeared.

“Gentlemen,” said he, in a tone strangely firm for a servant speaking to his masters under such solemn circumstances,—“gentlemen, M. Noirtier de Villefort wishes to speak immediately to M. Franz de Quesnel, baron d’Épinay.” He, as well as the notary, that there might be no mistake in the person, gave all his titles to the bridegroom elect.

Villefort started, Madame de Villefort let her son slip from her knees, Valentine rose, pale and dumb as a statue. Albert and Château-Renaud exchanged a second look, more full of amazement than the first. The notary looked at Villefort.

“It is impossible,” said the procureur. “M. d’Épinay cannot leave the drawing-room at present.”

“It is at this moment,” replied Barrois with the same firmness, “that M. Noirtier, my master, wishes to speak on important subjects to M. Franz d’Épinay.”

“Grandpapa Noirtier can speak now, then,” said Edward, with his habitual quickness. However, his remark did not make Madame de Villefort even smile, so much was every mind engaged, and so solemn was the situation.

“Tell M. Nortier,” resumed Villefort, “that what he demands is impossible.”

“Then, M. Nortier gives notice to these gentlemen,” replied Barrois, “that he will give orders to be carried to the drawing-room.”

Astonishment was at its height. Something like a smile was perceptible on Madame de Villefort’s countenance. Valentine instinctively raised her eyes, as if to thank heaven.

“Pray go, Valentine,” said; M. de Villefort, “and see what this new fancy of your grandfather’s is.” Valentine rose quickly, and was hastening joyfully towards the door, when M. de Villefort altered his intention.

“Stop,” said he; “I will go with you.”

“Excuse me, sir,” said Franz, “since M. Noirtier sent for me, I am ready to attend to his wish; besides, I shall be happy to pay my respects to him, not having yet had the honor of doing so.”

“Pray, sir,” said Villefort with marked uneasiness, “do not disturb yourself.”

“Forgive me, sir,” said Franz in a resolute tone. “I would not lose this opportunity of proving to M. Noirtier how wrong it would be of him to encourage feelings of dislike to me, which I am determined to conquer, whatever they may be, by my devotion.”

And without listening to Villefort he arose, and followed Valentine, who was running downstairs with the joy of a shipwrecked mariner who finds a rock to cling to. M. de Villefort followed them. Château-Renaud and Morcerf exchanged a third look of still increasing wonder.

Chapter 75. A Signed Statement

Noirtier was prepared to receive them, dressed in black, and installed in his armchair. When the three persons he expected had entered, he looked at the door, which his valet immediately closed.

“Listen,” whispered Villefort to Valentine, who could not conceal her joy; “if M. Noirtier wishes to communicate anything which would delay your marriage, I forbid you to understand him.”

Valentine blushed, but did not answer. Villefort, approached Noirtier.

“Here is M. Franz d’Épinay,” said he; “you requested to see him. We have all wished for this interview, and I trust it will convince you how ill-formed are your objections to Valentine’s marriage.”

Noirtier answered only by a look which made Villefort’s blood run cold. He motioned to Valentine to approach. In a moment, thanks to her habit of conversing with her grandfather, she understood that he asked for a key. Then his eye was fixed on the drawer of a small chest between the windows. She opened the drawer, and found a key; and, understanding that was what he wanted, again watched his eyes, which turned toward an old secretaire which had been neglected for many years and was supposed to contain nothing but useless documents.

“Shall I open the secretaire?” asked Valentine.

“Yes,” said the old man.

“And the drawers?”

“Yes.”

“Those at the side?”

“No.”

“The middle one?”

“Yes.”

Valentine opened it and drew out a bundle of papers. “Is that what you wish for?” asked she.

“No.”

She took successively all the other papers out till the drawer was empty. “But there are no more,” said she. Noirtier’s eye was fixed on the dictionary.

“Yes, I understand, grandfather,” said the young girl.

She pointed to each letter of the alphabet. At the letter S the old man stopped her. She opened, and found the word “secret.”

“Ah! is there a secret spring?” said Valentine.

“Yes,” said Noirtier.

“And who knows it?” Noirtier looked at the door where the servant had gone out.

“Barrois?” said she.

“Yes.”

“Shall I call him?”

“Yes.”

Valentine went to the door, and called Barrois. Villefort’s impatience during this scene made the perspiration roll from his forehead, and Franz was stupefied. The old servant came.

“Barrois,” said Valentine, “my grandfather has told me to open that drawer in the secretaire, but there is a secret spring in it, which you know—will you open it?”

Barrois looked at the old man. “Obey,” said Noirtier’s intelligent eye. Barrois touched a spring, the false bottom came out, and they saw a bundle of papers tied with a black string.

“Is that what you wish for?” said Barrois.

“Yes.”

“Shall I give these papers to M. de Villefort?”

“No.”

“To Mademoiselle Valentine?”

“No.”

“To M. Franz d’Épinay?”

“Yes.”

Franz, astonished, advanced a step. “To me, sir?” said he.

“Yes.”

Franz took them from Barrois and casting a glance at the cover, read:

“‘To be given, after my death, to General Durand, who shall bequeath the packet to his son, with an injunction to preserve it as containing an important document.’

“Well, sir,” asked Franz, “what do you wish me to do with this paper?”

“To preserve it, sealed up as it is, doubtless,” said the procureur.

“No,” replied Noirtier eagerly.

“Do you wish him to read it?” said Valentine.

“Yes,” replied the old man.

“You understand, baron, my grandfather wishes you to read this paper,” said Valentine.

“Then let us sit down,” said Villefort impatiently, “for it will take some time.”

“Sit down,” said the old man. Villefort took a chair, but Valentine remained standing by her father’s side, and Franz before him, holding the mysterious paper in his hand. “Read,” said the old man. Franz untied it, and in the midst of the most profound silence read:

“‘Extract of the report of a meeting of the Bonapartist Club in the Rue Saint-Jacques, held February 5th, 1815.’”

Franz stopped. “February 5th, 1815!” said he; “it is the day my father was murdered.” Valentine and Villefort were dumb; the eye of the old man alone seemed to say clearly, “Go on.”

“But it was on leaving this club,” said he, “my father disappeared.”

Noirtier’s eye continued to say, “Read.” He resumed:—

“‘The undersigned Louis-Jacques Beaurepaire, lieutenant-colonel of artillery, Étienne Duchampy, general of brigade, and Claude Lecharpal, keeper of woods and forests, declare, that on the 4th of February, a letter arrived from the Island of Elba, recommending to the kindness and the confidence of the Bonapartist Club, General Flavien de Quesnel, who having served the emperor from 1804 to 1814 was supposed to be devoted to the interests of the Napoleon dynasty, notwithstanding the title of baron which Louis XVIII. had just granted to him with his estate of Épinay.

“‘A note was in consequence addressed to General de Quesnel, begging him to be present at the meeting next day, the 5th. The note indicated neither the street nor the number of the house where the meeting was to be held; it bore no signature, but it announced to the general that someone would call for him if he would be ready at nine o’clock. The meetings were always held from that time till midnight. At nine o’clock the president of the club presented himself; the general was ready, the president informed him that one of the conditions of his introduction was that he should be eternally ignorant of the place of meeting, and that he would allow his eyes to be bandaged, swearing that he would not endeavor to take off the bandage. General de Quesnel accepted the condition, and promised on his honor not to seek to discover the road they took. The general’s carriage was ready, but the president told him it was impossible for him to use it, since it was useless to blindfold the master if the coachman knew through what streets he went. “What must be done then?” asked the general.—“I have my carriage here,” said the president.

“‘“Have you, then, so much confidence in your servant that you can intrust him with a secret you will not allow me to know?”

“‘“Our coachman is a member of the club,” said the president; “we shall be driven by a State-Councillor.”

“‘“Then we run another risk,” said the general, laughing, “that of being upset.” We insert this joke to prove that the general was not in the least compelled to attend the meeting, but that he came willingly. When they were seated in the carriage the president reminded the general of his promise to allow his eyes to be bandaged, to which he made no opposition. On the road the president thought he saw the general make an attempt to remove the handkerchief, and reminded him of his oath. “Sure enough,” said the general. The carriage stopped at an alley leading out of the Rue Saint-Jacques. The general alighted, leaning on the arm of the president, of whose dignity he was not aware, considering him simply as a member of the club; they went through the alley, mounted a flight of stairs, and entered the assembly-room.

“‘The deliberations had already begun. The members, apprised of the sort of presentation which was to be made that evening, were all in attendance. When in the middle of the room the general was invited to remove his bandage, he did so immediately, and was surprised to see so many well-known faces in a society of whose existence he had till then been ignorant. They questioned him as to his sentiments, but he contented himself with answering, that the letters from the Island of Elba ought to have informed them——’”

Franz interrupted himself by saying, “My father was a royalist; they need not have asked his sentiments, which were well known.”

“And hence,” said Villefort, “arose my affection for your father, my dear M. Franz. Opinions held in common are a ready bond of union.”

“Read again,” said the old man.

Franz continued:

“‘The president then sought to make him speak more explicitly, but M. de Quesnel replied that he wished first to know what they wanted with him. He was then informed of the contents of the letter from the Island of Elba, in which he was recommended to the club as a man who would be likely to advance the interests of their party. One paragraph spoke of the return of Bonaparte and promised another letter and further details, on the arrival of the Pharaon belonging to the shipbuilder Morrel, of Marseilles, whose captain was entirely devoted to the emperor. During all this time, the general, on whom they thought to have relied as on a brother, manifested evidently signs of discontent and repugnance. When the reading was finished, he remained silent, with knitted brows.

“‘“Well,” asked the president, “what do you say to this letter, general?”

“‘“I say that it is too soon after declaring myself for Louis XVIII. to break my vow in behalf of the ex-emperor.” This answer was too clear to permit of any mistake as to his sentiments. “General,” said the president, “we acknowledge no King Louis XVIII., or an ex-emperor, but his majesty the emperor and king, driven from France, which is his kingdom, by violence and treason.”

“‘“Excuse me, gentlemen,” said the general; “you may not acknowledge Louis XVIII., but I do, as he has made me a baron and a field-marshal, and I shall never forget that for these two titles I am indebted to his happy return to France.”

“‘“Sir,” said the president, rising with gravity, “be careful what you say; your words clearly show us that they are deceived concerning you in the Island of Elba, and have deceived us! The communication has been made to you in consequence of the confidence placed in you, and which does you honor. Now we discover our error; a title and promotion attach you to the government we wish to overturn. We will not constrain you to help us; we enroll no one against his conscience, but we will compel you to act generously, even if you are not disposed to do so.”

“‘“You would call acting generously, knowing your conspiracy and not informing against you, that is what I should call becoming your accomplice. You see I am more candid than you.”’”

“Ah, my father!” said Franz, interrupting himself. “I understand now why they murdered him.” Valentine could not help casting one glance towards the young man, whose filial enthusiasm it was delightful to behold. Villefort walked to and fro behind them. Noirtier watched the expression of each one, and preserved his dignified and commanding attitude. Franz returned to the manuscript, and continued:

“‘“Sir,” said the president, “you have been invited to join this assembly—you were not forced here; it was proposed to you to come blindfolded—you accepted. When you complied with this twofold request you well knew we did not wish to secure the throne of Louis XVIII., or we should not take so much care to avoid the vigilance of the police. It would be conceding too much to allow you to put on a mask to aid you in the discovery of our secret, and then to remove it that you may ruin those who have confided in you. No, no, you must first say if you declare yourself for the king of a day who now reigns, or for his majesty the emperor.”

“‘“I am a royalist,” replied the general; “I have taken the oath of allegiance to Louis XVIII., and I will adhere to it.” These words were followed by a general murmur, and it was evident that several of the members were discussing the propriety of making the general repent of his rashness.

“‘The president again arose, and having imposed silence, said,—“Sir, you are too serious and too sensible a man not to understand the consequences of our present situation, and your candor has already dictated to us the conditions which remain for us to offer you.” The general, putting his hand on his sword, exclaimed,—“If you talk of honor, do not begin by disavowing its laws, and impose nothing by violence.”

“‘“And you, sir,” continued the president, with a calmness still more terrible than the general’s anger, “I advise you not to touch your sword.” The general looked around him with slight uneasiness; however he did not yield, but calling up all his fortitude, said,—“I will not swear.”

“‘“Then you must die,” replied the president calmly. M. d’Épinay became very pale; he looked round him a second time, several members of the club were whispering, and getting their arms from under their cloaks. “General,” said the president, “do not alarm yourself; you are among men of honor who will use every means to convince you before resorting to the last extremity, but as you have said, you are among conspirators, you are in possession of our secret, and you must restore it to us.” A significant silence followed these words, and as the general did not reply,—“Close the doors,” said the president to the door-keeper.

“‘The same deadly silence succeeded these words. Then the general advanced, and making a violent effort to control his feelings,—“I have a son,” said he, “and I ought to think of him, finding myself among assassins.”

“‘“General,” said the chief of the assembly, “one man may insult fifty—it is the privilege of weakness. But he does wrong to use his privilege. Follow my advice, swear, and do not insult.” The general, again daunted by the superiority of the chief, hesitated a moment; then advancing to the president’s desk,—“What is the form, said he.

“‘“It is this:—‘I swear by my honor not to reveal to anyone what I have seen and heard on the 5th of February, 1815, between nine and ten o’clock in the evening; and I plead guilty of death should I ever violate this oath.’” The general appeared to be affected by a nervous tremor, which prevented his answering for some moments; then, overcoming his manifest repugnance, he pronounced the required oath, but in so low a tone as to be scarcely audible to the majority of the members, who insisted on his repeating it clearly and distinctly, which he did.

“‘“Now am I at liberty to retire?” said the general. The president rose, appointed three members to accompany him, and got into the carriage with the general after bandaging his eyes. One of those three members was the coachman who had driven them there. The other members silently dispersed. “Where do you wish to be taken?” asked the president.—“Anywhere out of your presence,” replied M. d’Épinay. “Beware, sir,” replied the president, “you are no longer in the assembly, and have only to do with individuals; do not insult them unless you wish to be held responsible.” But instead of listening, M. d’Épinay went on,—“You are still as brave in your carriage as in your assembly because you are still four against one.” The president stopped the coach. They were at that part of the Quai des Ormes where the steps lead down to the river. “Why do you stop here?” asked d’Épinay.

“‘“Because, sir,” said the president, “you have insulted a man, and that man will not go one step farther without demanding honorable reparation.”

“‘“Another method of assassination?” said the general, shrugging his shoulders.

“‘“Make no noise, sir, unless you wish me to consider you as one of the men of whom you spoke just now as cowards, who take their weakness for a shield. You are alone, one alone shall answer you; you have a sword by your side, I have one in my cane; you have no witness, one of these gentlemen will serve you. Now, if you please, remove your bandage.” The general tore the handkerchief from his eyes. “At last,” said he, “I shall know with whom I have to do.” They opened the door and the four men alighted.’”

Franz again interrupted himself, and wiped the cold drops from his brow; there was something awful in hearing the son read aloud in trembling pallor these details of his father’s death, which had hitherto been a mystery. Valentine clasped her hands as if in prayer. Noirtier looked at Villefort with an almost sublime expression of contempt and pride.

Franz continued:

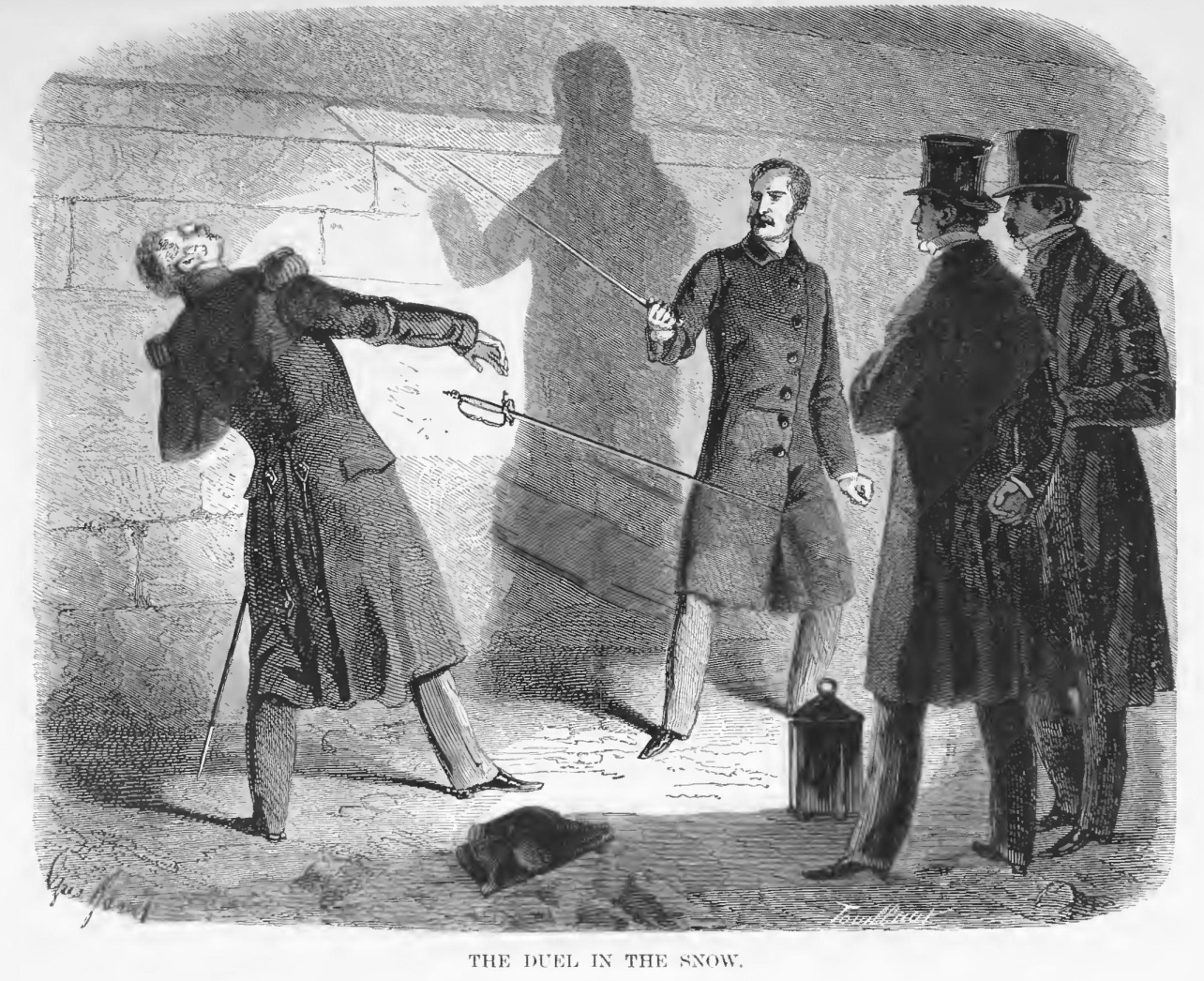

“‘It was, as we said, the fifth of February. For three days the mercury had been five or six degrees below freezing and the steps were covered with ice. The general was stout and tall, the president offered him the side of the railing to assist him in getting down. The two witnesses followed. It was a dark night. The ground from the steps to the river was covered with snow and hoarfrost, the water of the river looked black and deep. One of the seconds went for a lantern in a coal-barge near, and by its light they examined the weapons. The president’s sword, which was simply, as he had said, one he carried in his cane, was five inches shorter than the general’s, and had no guard. The general proposed to cast lots for the swords, but the president said it was he who had given the provocation, and when he had given it he had supposed each would use his own arms. The witnesses endeavored to insist, but the president bade them be silent. The lantern was placed on the ground, the two adversaries took their stations, and the duel began. The light made the two swords appear like flashes of lightning; as for the men, they were scarcely perceptible, the darkness was so great.

“‘General d’Épinay passed for one of the best swordsmen in the army, but he was pressed so closely in the onset that he missed his aim and fell. The witnesses thought he was dead, but his adversary, who knew he had not struck him, offered him the assistance of his hand to rise. The circumstance irritated instead of calming the general, and he rushed on his adversary. But his opponent did not allow his guard to be broken. He received him on his sword and three times the general drew back on finding himself too closely engaged, and then returned to the charge. At the third he fell again. They thought he slipped, as at first, and the witnesses, seeing he did not move, approached and endeavored to raise him, but the one who passed his arm around the body found it was moistened with blood. The general, who had almost fainted, revived. “Ah,” said he, “they have sent some fencing-master to fight with me.” The president, without answering, approached the witness who held the lantern, and raising his sleeve, showed him two wounds he had received in his arm; then opening his coat, and unbuttoning his waistcoat, displayed his side, pierced with a third wound. Still he had not even uttered a sigh. General d’Épinay died five minutes after.’”

Franz read these last words in a voice so choked that they were hardly audible, and then stopped, passing his hand over his eyes as if to dispel a cloud; but after a moment’s silence, he continued:

“‘The president went up the steps, after pushing his sword into his cane; a track of blood on the snow marked his course. He had scarcely arrived at the top when he heard a heavy splash in the water—it was the general’s body, which the witnesses had just thrown into the river after ascertaining that he was dead. The general fell, then, in a loyal duel, and not in ambush as it might have been reported. In proof of this we have signed this paper to establish the truth of the facts, lest the moment should arrive when either of the actors in this terrible scene should be accused of premeditated murder or of infringement of the laws of honor.

“‘Signed, Beaurepaire, Duchampy, and Lecharpal.’”

When Franz had finished reading this account, so dreadful for a son; when Valentine, pale with emotion, had wiped away a tear; when Villefort, trembling, and crouched in a corner, had endeavored to lessen the storm by supplicating glances at the implacable old man,—

“Sir,” said d’Épinay to Noirtier, “since you are well acquainted with all these details, which are attested by honorable signatures,—since you appear to take some interest in me, although you have only manifested it hitherto by causing me sorrow, refuse me not one final satisfaction—tell me the name of the president of the club, that I may at least know who killed my father.”

Villefort mechanically felt for the handle of the door; Valentine, who understood sooner than anyone her grandfather’s answer, and who had often seen two scars upon his right arm, drew back a few steps.

“Mademoiselle,” said Franz, turning towards Valentine, “unite your efforts with mine to find out the name of the man who made me an orphan at two years of age.” Valentine remained dumb and motionless.

“Hold, sir,” said Villefort, “do not prolong this dreadful scene. The names have been purposely concealed; my father himself does not know who this president was, and if he knows, he cannot tell you; proper names are not in the dictionary.”

“Oh, misery,” cried Franz: “the only hope which sustained me and enabled me to read to the end was that of knowing, at least, the name of him who killed my father! Sir, sir,” cried he, turning to Noirtier, “do what you can—make me understand in some way!”

“Yes,” replied Noirtier.

“Oh, mademoiselle, mademoiselle!” cried Franz, “your grandfather says he can indicate the person. Help me,—lend me your assistance!”

Noirtier looked at the dictionary. Franz took it with a nervous trembling, and repeated the letters of the alphabet successively, until he came to M. At that letter the old man signified “Yes.”

“M,” repeated Franz. The young man’s finger, glided over the words, but at each one Noirtier answered by a negative sign. Valentine hid her head between her hands. At length, Franz arrived at the word MYSELF.

“Yes!”

“You!” cried Franz, whose hair stood on end; “you, M. Noirtier—you killed my father?”

“Yes!” replied Noirtier, fixing a majestic look on the young man. Franz fell powerless on a chair; Villefort opened the door and escaped, for the idea had entered his mind to stifle the little remaining life in the heart of this terrible old man.

Chapter 76. Progress of Cavalcanti the Younger

Meanwhile M. Cavalcanti the elder had returned to his service, not in the army of his majesty the Emperor of Austria, but at the gaming-table of the baths of Lucca, of which he was one of the most assiduous courtiers. He had spent every farthing that had been allowed for his journey as a reward for the majestic and solemn manner in which he had maintained his assumed character of father.

M. Andrea at his departure inherited all the papers which proved that he had indeed the honor of being the son of the Marquis Bartolomeo and the Marchioness Oliva Corsinari. He was now fairly launched in that Parisian society which gives such ready access to foreigners, and treats them, not as they really are, but as they wish to be considered. Besides, what is required of a young man in Paris? To speak its language tolerably, to make a good appearance, to be a good gamester, and to pay in cash. They are certainly less particular with a foreigner than with a Frenchman. Andrea had, then, in a fortnight, attained a very fair position. He was called count, he was said to possess 50,000 livres per annum; and his father’s immense riches, buried in the quarries of Saravezza, were a constant theme. A learned man, before whom the last circumstance was mentioned as a fact, declared he had seen the quarries in question, which gave great weight to assertions hitherto somewhat doubtful, but which now assumed the garb of reality.

Such was the state of society in Paris at the period we bring before our readers, when Monte Cristo went one evening to pay M. Danglars a visit. M. Danglars was out, but the count was asked to go and see the baroness, and he accepted the invitation. It was never without a nervous shudder, since the dinner at Auteuil, and the events which followed it, that Madame Danglars heard Monte Cristo’s name announced. If he did not come, the painful sensation became most intense; if, on the contrary, he appeared, his noble countenance, his brilliant eyes, his amiability, his polite attention even towards Madame Danglars, soon dispelled every impression of fear. It appeared impossible to the baroness that a man of such delightfully pleasing manners should entertain evil designs against her; besides, the most corrupt minds only suspect evil when it would answer some interested end—useless injury is repugnant to every mind.

When Monte Cristo entered the boudoir, to which we have already once introduced our readers, and where the baroness was examining some drawings, which her daughter passed to her after having looked at them with M. Cavalcanti, his presence soon produced its usual effect, and it was with smiles that the baroness received the count, although she had been a little disconcerted at the announcement of his name. The latter took in the whole scene at a glance.

The baroness was partially reclining on a sofa, Eugénie sat near her, and Cavalcanti was standing. Cavalcanti, dressed in black, like one of Goethe’s heroes, with varnished shoes and white silk open-worked stockings, passed a white and tolerably nice-looking hand through his light hair, and so displayed a sparkling diamond, that in spite of Monte Cristo’s advice the vain young man had been unable to resist putting on his little finger. This movement was accompanied by killing glances at Mademoiselle Danglars, and by sighs launched in the same direction.

Mademoiselle Danglars was still the same—cold, beautiful, and satirical. Not one of these glances, nor one sigh, was lost on her; they might have been said to fall on the shield of Minerva, which some philosophers assert protected sometimes the breast of Sappho. Eugénie bowed coldly to the count, and availed herself of the first moment when the conversation became earnest to escape to her study, whence very soon two cheerful and noisy voices being heard in connection with occasional notes of the piano assured Monte Cristo that Mademoiselle Danglars preferred to his society and to that of M. Cavalcanti the company of Mademoiselle Louise d’Armilly, her singing teacher.

It was then, especially while conversing with Madame Danglars, and apparently absorbed by the charm of the conversation, that the count noticed M. Andrea Cavalcanti’s solicitude, his manner of listening to the music at the door he dared not pass, and of manifesting his admiration.

The banker soon returned. His first look was certainly directed towards Monte Cristo, but the second was for Andrea. As for his wife, he bowed to her, as some husbands do to their wives, but in a way that bachelors will never comprehend, until a very extensive code is published on conjugal life.

“Have not the ladies invited you to join them at the piano?” said Danglars to Andrea.

“Alas, no, sir,” replied Andrea with a sigh, still more remarkable than the former ones. Danglars immediately advanced towards the door and opened it.

The two young ladies were seen seated on the same chair, at the piano, accompanying themselves, each with one hand, a fancy to which they had accustomed themselves, and performed admirably. Mademoiselle d’Armilly, whom they then perceived through the open doorway, formed with Eugénie one of the tableaux vivants of which the Germans are so fond. She was somewhat beautiful, and exquisitely formed—a little fairy-like figure, with large curls falling on her neck, which was rather too long, as Perugino sometimes makes his Virgins, and her eyes dull from fatigue. She was said to have a weak chest, and like Antonia in the Cremona Violin, she would die one day while singing.

Monte Cristo cast one rapid and curious glance round this sanctum; it was the first time he had ever seen Mademoiselle d’Armilly, of whom he had heard much.

“Well,” said the banker to his daughter, “are we then all to be excluded?”

He then led the young man into the study, and either by chance or manœuvre the door was partially closed after Andrea, so that from the place where they sat neither the Count nor the baroness could see anything; but as the banker had accompanied Andrea, Madame Danglars appeared to take no notice of it.

The count soon heard Andrea’s voice, singing a Corsican song, accompanied by the piano. While the count smiled at hearing this song, which made him lose sight of Andrea in the recollection of Benedetto, Madame Danglars was boasting to Monte Cristo of her husband’s strength of mind, who that very morning had lost three or four hundred thousand francs by a failure at Milan. The praise was well deserved, for had not the count heard it from the baroness, or by one of those means by which he knew everything, the baron’s countenance would not have led him to suspect it.

“Hem,” thought Monte Cristo, “he begins to conceal his losses; a month since he boasted of them.”

Then aloud,—“Oh, madame, M. Danglars is so skilful, he will soon regain at the Bourse what he loses elsewhere.”

“I see that you participate in a prevalent error,” said Madame Danglars.

“What is it?” said Monte Cristo.

“That M. Danglars speculates, whereas he never does.”

“Truly, madame, I recollect M. Debray told me——apropos, what has become of him? I have seen nothing of him the last three or four days.”

“Nor I,” said Madame Danglars; “but you began a sentence, sir, and did not finish.”

“Which?”

“M. Debray had told you——”

“Ah, yes; he told me it was you who sacrificed to the demon of speculation.”

“I was once very fond of it, but I do not indulge now.”

“Then you are wrong, madame. Fortune is precarious; and if I were a woman and fate had made me a banker’s wife, whatever might be my confidence in my husband’s good fortune, still in speculation you know there is great risk. Well, I would secure for myself a fortune independent of him, even if I acquired it by placing my interests in hands unknown to him.” Madame Danglars blushed, in spite of all her efforts.

“Stay,” said Monte Cristo, as though he had not observed her confusion, “I have heard of a lucky hit that was made yesterday on the Neapolitan bonds.”

“I have none—nor have I ever possessed any; but really we have talked long enough of money, count, we are like two stockbrokers; have you heard how fate is persecuting the poor Villeforts?”

“What has happened?” said the count, simulating total ignorance.

“You know the Marquis of Saint-Méran died a few days after he had set out on his journey to Paris, and the marchioness a few days after her arrival?”

“Yes,” said Monte Cristo, “I have heard that; but, as Claudius said to Hamlet, ‘it is a law of nature; their fathers died before them, and they mourned their loss; they will die before their children, who will, in their turn, grieve for them.’”

“But that is not all.”

“Not all!”

“No; they were going to marry their daughter——”

“To M. Franz d’Épinay. Is it broken off?”

“Yesterday morning, it appears, Franz declined the honor.”

“Indeed? And is the reason known?”

“No.”

“How extraordinary! And how does M. de Villefort bear it?”

“As usual. Like a philosopher.”

Danglars returned at this moment alone.

“Well,” said the baroness, “do you leave M. Cavalcanti with your daughter?”

“And Mademoiselle d’Armilly,” said the banker; “do you consider her no one?” Then, turning to Monte Cristo, he said, “Prince Cavalcanti is a charming young man, is he not? But is he really a prince?”

“I will not answer for it,” said Monte Cristo. “His father was introduced to me as a marquis, so he ought to be a count; but I do not think he has much claim to that title.”

“Why?” said the banker. “If he is a prince, he is wrong not to maintain his rank; I do not like anyone to deny his origin.”

“Oh, you are a thorough democrat,” said Monte Cristo, smiling.

“But do you see to what you are exposing yourself?” said the baroness. “If, perchance, M. de Morcerf came, he would find M. Cavalcanti in that room, where he, the betrothed of Eugénie, has never been admitted.”

“You may well say, perchance,” replied the banker; “for he comes so seldom, it would seem only chance that brings him.”

“But should he come and find that young man with your daughter, he might be displeased.”

“He? You are mistaken. M. Albert would not do us the honor to be jealous; he does not like Eugénie sufficiently. Besides, I care not for his displeasure.”

“Still, situated as we are——”

“Yes, do you know how we are situated? At his mother’s ball he danced once with Eugénie, and M. Cavalcanti three times, and he took no notice of it.”

The valet announced the Vicomte Albert de Morcerf. The baroness rose hastily, and was going into the study, when Danglars stopped her.

“Let her alone,” said he.

She looked at him in amazement. Monte Cristo appeared to be unconscious of what passed. Albert entered, looking very handsome and in high spirits. He bowed politely to the baroness, familiarly to Danglars, and affectionately to Monte Cristo. Then turning to the baroness: “May I ask how Mademoiselle Danglars is?” said he.

“She is quite well,” replied Danglars quickly; “she is at the piano with M. Cavalcanti.”

Albert retained his calm and indifferent manner; he might feel perhaps annoyed, but he knew Monte Cristo’s eye was on him. “M. Cavalcanti has a fine tenor voice,” said he, “and Mademoiselle Eugénie a splendid soprano, and then she plays the piano like Thalberg. The concert must be a delightful one.”

“They suit each other remarkably well,” said Danglars. Albert appeared not to notice this remark, which was, however, so rude that Madame Danglars blushed.

“I, too,” said the young man, “am a musician—at least, my masters used to tell me so; but it is strange that my voice never would suit any other, and a soprano less than any.”

Danglars smiled, and seemed to say, “It is of no consequence.” Then, hoping doubtless to effect his purpose, he said,—“The prince and my daughter were universally admired yesterday. You were not of the party, M. de Morcerf?”

“What prince?” asked Albert.

“Prince Cavalcanti,” said Danglars, who persisted in giving the young man that title.

“Pardon me,” said Albert, “I was not aware that he was a prince. And Prince Cavalcanti sang with Mademoiselle Eugénie yesterday? It must have been charming, indeed. I regret not having heard them. But I was unable to accept your invitation, having promised to accompany my mother to a German concert given by the Baroness of Château-Renaud.”

This was followed by rather an awkward silence.

“May I also be allowed,” said Morcerf, “to pay my respects to Mademoiselle Danglars?”

“Wait a moment,” said the banker, stopping the young man; “do you hear that delightful cavatina? Ta, ta, ta, ti, ta, ti, ta, ta; it is charming, let them finish—one moment. Bravo, bravi, brava!” The banker was enthusiastic in his applause.

“Indeed,” said Albert, “it is exquisite; it is impossible to understand the music of his country better than Prince Cavalcanti does. You said prince, did you not? But he can easily become one, if he is not already; it is no uncommon thing in Italy. But to return to the charming musicians—you should give us a treat, Danglars, without telling them there is a stranger. Ask them to sing one more song; it is so delightful to hear music in the distance, when the musicians are unrestrained by observation.”

Danglars was quite annoyed by the young man’s indifference. He took Monte Cristo aside.

“What do you think of our lover?” said he.

“He appears cool. But, then your word is given.”

“Yes, doubtless I have promised to give my daughter to a man who loves her, but not to one who does not. See him there, cold as marble and proud like his father. If he were rich, if he had Cavalcanti’s fortune, that might be pardoned. Ma foi, I haven’t consulted my daughter; but if she has good taste——”

“Oh,” said Monte Cristo, “my fondness may blind me, but I assure you I consider Morcerf a charming young man who will render your daughter happy and will sooner or later attain a certain amount of distinction, and his father’s position is good.”

“Hem,” said Danglars.

“Why do you doubt?”

“The past—that obscurity on the past.”

“But that does not affect the son.”

“Very true.”

“Now, I beg of you, don’t go off your head. It’s a month now that you have been thinking of this marriage, and you must see that it throws some responsibility on me, for it was at my house you met this young Cavalcanti, whom I do not really know at all.”

“But I do.”

“Have you made inquiry?”

“Is there any need of that! Does not his appearance speak for him? And he is very rich.”

“I am not so sure of that.”

“And yet you said he had money.”

“Fifty thousand livres—a mere trifle.”

“He is well educated.”

“Hem,” said Monte Cristo in his turn.

“He is a musician.”

“So are all Italians.”

“Come, count, you do not do that young man justice.”

“Well, I acknowledge it annoys me, knowing your connection with the Morcerf family, to see him throw himself in the way.” Danglars burst out laughing.

“What a Puritan you are!” said he; “that happens every day.”

“But you cannot break it off in this way; the Morcerfs are depending on this union.”

“Indeed.”

“Positively.”

“Then let them explain themselves; you should give the father a hint, you are so intimate with the family.”

“I?—where the devil did you find out that?”

“At their ball; it was apparent enough. Why, did not the countess, the proud Mercédès, the disdainful Catalane, who will scarcely open her lips to her oldest acquaintances, take your arm, lead you into the garden, into the private walks, and remain there for half an hour?”

“Ah, baron, baron,” said Albert, “you are not listening—what barbarism in a megalomaniac like you!”

“Oh, don’t worry about me, Sir Mocker,” said Danglars; then turning to Monte Cristo he said:

“But will you undertake to speak to the father?”

“Willingly, if you wish it.”

“But let it be done explicitly and positively. If he demands my daughter let him fix the day—declare his conditions; in short, let us either understand each other, or quarrel. You understand—no more delay.”

“Yes, sir, I will give my attention to the subject.”

“I do not say that I await with pleasure his decision, but I do await it. A banker must, you know, be a slave to his promise.” And Danglars sighed as M. Cavalcanti had done half an hour before.

“Bravi! bravo! brava!” cried Morcerf, parodying the banker, as the selection came to an end. Danglars began to look suspiciously at Morcerf, when someone came and whispered a few words to him.

“I shall soon return,” said the banker to Monte Cristo; “wait for me. I shall, perhaps, have something to say to you.” And he went out.

The baroness took advantage of her husband’s absence to push open the door of her daughter’s study, and M. Andrea, who was sitting before the piano with Mademoiselle Eugénie, started up like a jack-in-the-box. Albert bowed with a smile to Mademoiselle Danglars, who did not appear in the least disturbed, and returned his bow with her usual coolness. Cavalcanti was evidently embarrassed; he bowed to Morcerf, who replied with the most impertinent look possible. Then Albert launched out in praise of Mademoiselle Danglars’ voice, and on his regret, after what he had just heard, that he had been unable to be present the previous evening.

Cavalcanti, being left alone, turned to Monte Cristo.

“Come,” said Madame Danglars, “leave music and compliments, and let us go and take tea.”

“Come, Louise,” said Mademoiselle Danglars to her friend.

They passed into the next drawing-room, where tea was prepared. Just as they were beginning, in the English fashion, to leave the spoons in their cups, the door again opened and Danglars entered, visibly agitated. Monte Cristo observed it particularly, and by a look asked the banker for an explanation.

“I have just received my courier from Greece,” said Danglars.

“Ah, yes,” said the count; “that was the reason of your running away from us.”

“Yes.”

“How is King Otho getting on?” asked Albert in the most sprightly tone.

Danglars cast another suspicious look towards him without answering, and Monte Cristo turned away to conceal the expression of pity which passed over his features, but which was gone in a moment.

“We shall go together, shall we not?” said Albert to the count.

“If you like,” replied the latter.

Albert could not understand the banker’s look, and turning to Monte Cristo, who understood it perfectly,—“Did you see,” said he, “how he looked at me?”

“Yes,” said the count; “but did you think there was anything particular in his look?”

“Indeed, I did; and what does he mean by his news from Greece?”

“How can I tell you?”

“Because I imagine you have correspondents in that country.”

Monte Cristo smiled significantly.

“Stop,” said Albert, “here he comes. I shall compliment Mademoiselle Danglars on her cameo, while the father talks to you.”

“If you compliment her at all, let it be on her voice, at least,” said Monte Cristo.

“No, everyone would do that.”

“My dear viscount, you are dreadfully impertinent.”

Albert advanced towards Eugénie, smiling.

Meanwhile, Danglars, stooping to Monte Cristo’s ear, “Your advice was excellent,” said he; “there is a whole history connected with the names Fernand and Yanina.”

“Indeed?” said Monte Cristo.

“Yes, I will tell you all; but take away the young man; I cannot endure his presence.”

“He is going with me. Shall I send the father to you?”

“Immediately.”

“Very well.” The count made a sign to Albert and they bowed to the ladies, and took their leave, Albert perfectly indifferent to Mademoiselle Danglars’ contempt, Monte Cristo reiterating his advice to Madame Danglars on the prudence a banker’s wife should exercise in providing for the future.

M. Cavalcanti remained master of the field.

Chapter 77. Haydée

Scarcely had the count’s horses cleared the angle of the boulevard, when Albert, turning towards the count, burst into a loud fit of laughter—much too loud in fact not to give the idea of its being rather forced and unnatural.

“Well,” said he, “I will ask you the same question which Charles IX. put to Catherine de’ Medici, after the massacre of Saint Bartholomew: ‘How have I played my little part?’”

“To what do you allude?” asked Monte Cristo.

“To the installation of my rival at M. Danglars’.”

“What rival?”

“Ma foi! what rival? Why, your protégé, M. Andrea Cavalcanti!”

“Ah, no joking, viscount, if you please; I do not patronize M. Andrea—at least, not as concerns M. Danglars.”

“And you would be to blame for not assisting him, if the young man really needed your help in that quarter, but, happily for me, he can dispense with it.”

“What, do you think he is paying his addresses?”

“I am certain of it; his languishing looks and modulated tones when addressing Mademoiselle Danglars fully proclaim his intentions. He aspires to the hand of the proud Eugénie.”

“What does that signify, so long as they favor your suit?”

“But it is not the case, my dear count: on the contrary. I am repulsed on all sides.”

“What!”

“It is so indeed; Mademoiselle Eugénie scarcely answers me, and Mademoiselle d’Armilly, her confidant, does not speak to me at all.”

“But the father has the greatest regard possible for you,” said Monte Cristo.

“He? Oh, no, he has plunged a thousand daggers into my heart, tragedy-weapons, I own, which instead of wounding sheathe their points in their own handles, but daggers which he nevertheless believed to be real and deadly.”

“Jealousy indicates affection.”

“True; but I am not jealous.”

“He is.”

“Of whom?—of Debray?”

“No, of you.”

“Of me? I will engage to say that before a week is past the door will be closed against me.”

“You are mistaken, my dear viscount.”

“Prove it to me.”

“Do you wish me to do so?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I am charged with the commission of endeavoring to induce the Comte de Morcerf to make some definite arrangement with the baron.”

“By whom are you charged?”

“By the baron himself.”

“Oh,” said Albert with all the cajolery of which he was capable. “You surely will not do that, my dear count?”

“Certainly I shall, Albert, as I have promised to do it.”

“Well,” said Albert, with a sigh, “it seems you are determined to marry me.”

“I am determined to try and be on good terms with everybody, at all events,” said Monte Cristo. “But apropos of Debray, how is it that I have not seen him lately at the baron’s house?”

“There has been a misunderstanding.”

“What, with the baroness?”

“No, with the baron.”

“Has he perceived anything?”

“Ah, that is a good joke!”

“Do you think he suspects?” said Monte Cristo with charming artlessness.

“Where have you come from, my dear count?” said Albert.

“From Congo, if you will.”

“It must be farther off than even that.”

“But what do I know of your Parisian husbands?”

“Oh, my dear count, husbands are pretty much the same everywhere; an individual husband of any country is a pretty fair specimen of the whole race.”

“But then, what can have led to the quarrel between Danglars and Debray? They seemed to understand each other so well,” said Monte Cristo with renewed energy.

“Ah, now you are trying to penetrate into the mysteries of Isis, in which I am not initiated. When M. Andrea Cavalcanti has become one of the family, you can ask him that question.”

The carriage stopped.

“Here we are,” said Monte Cristo; “it is only half-past ten o’clock, come in.”

“Certainly, I will.”

“My carriage shall take you back.”

“No, thank you; I gave orders for my coupé to follow me.”

“There it is, then,” said Monte Cristo, as he stepped out of the carriage. They both went into the house; the drawing-room was lighted up—they went in there. “You will make tea for us, Baptistin,” said the count. Baptistin left the room without waiting to answer, and in two seconds reappeared, bringing on a tray, all that his master had ordered, ready prepared, and appearing to have sprung from the ground, like the repasts which we read of in fairy tales.

“Really, my dear count,” said Morcerf, “what I admire in you is, not so much your riches, for perhaps there are people even wealthier than yourself, nor is it only your wit, for Beaumarchais might have possessed as much,—but it is your manner of being served, without any questions, in a moment, in a second; it is as if they guessed what you wanted by your manner of ringing, and made a point of keeping everything you can possibly desire in constant readiness.”

“What you say is perhaps true; they know my habits. For instance, you shall see; how do you wish to occupy yourself during tea-time?”

“Ma foi, I should like to smoke.”

Monte Cristo took the gong and struck it once. In about the space of a second a private door opened, and Ali appeared, bringing two chibouques filled with excellent latakia.

“It is quite wonderful,” said Albert.

“Oh no, it is as simple as possible,” replied Monte Cristo. “Ali knows I generally smoke while I am taking my tea or coffee; he has heard that I ordered tea, and he also knows that I brought you home with me; when I summoned him he naturally guessed the reason of my doing so, and as he comes from a country where hospitality is especially manifested through the medium of smoking, he naturally concludes that we shall smoke in company, and therefore brings two chibouques instead of one—and now the mystery is solved.”

“Certainly you give a most commonplace air to your explanation, but it is not the less true that you——Ah, but what do I hear?” and Morcerf inclined his head towards the door, through which sounds seemed to issue resembling those of a guitar.

“Ma foi, my dear viscount, you are fated to hear music this evening; you have only escaped from Mademoiselle Danglars’ piano, to be attacked by Haydée’s guzla.”

“Haydée—what an adorable name! Are there, then, really women who bear the name of Haydée anywhere but in Byron’s poems?”

“Certainly there are. Haydée is a very uncommon name in France, but is common enough in Albania and Epirus; it is as if you said, for example, Chastity, Modesty, Innocence,—it is a kind of baptismal name, as you Parisians call it.”

“Oh, that is charming,” said Albert, “how I should like to hear my countrywomen called Mademoiselle Goodness, Mademoiselle Silence, Mademoiselle Christian Charity! Only think, then, if Mademoiselle Danglars, instead of being called Claire-Marie-Eugénie, had been named Mademoiselle Chastity-Modesty-Innocence Danglars; what a fine effect that would have produced on the announcement of her marriage!”

“Hush,” said the count, “do not joke in so loud a tone; Haydée may hear you, perhaps.”

“And you think she would be angry?”

“No, certainly not,” said the count with a haughty expression.

“She is very amiable, then, is she not?” said Albert.

“It is not to be called amiability, it is her duty; a slave does not dictate to a master.”

“Come; you are joking yourself now. Are there any more slaves to be had who bear this beautiful name?”

“Undoubtedly.”

“Really, count, you do nothing, and have nothing like other people. The slave of the Count of Monte Cristo! Why, it is a rank of itself in France, and from the way in which you lavish money, it is a place that must be worth a hundred thousand francs a year.”

“A hundred thousand francs! The poor girl originally possessed much more than that; she was born to treasures in comparison with which those recorded in the Thousand and One Nights would seem but poverty.”

“She must be a princess then.”

“You are right; and she is one of the greatest in her country too.”

“I thought so. But how did it happen that such a great princess became a slave?”

“How was it that Dionysius the Tyrant became a schoolmaster? The fortune of war, my dear viscount,—the caprice of fortune; that is the way in which these things are to be accounted for.”

“And is her name a secret?”

“As regards the generality of mankind it is; but not for you, my dear viscount, who are one of my most intimate friends, and on whose silence I feel I may rely, if I consider it necessary to enjoin it—may I not do so?”

“Certainly; on my word of honor.”

“You know the history of the Pasha of Yanina, do you not?”

“Of Ali Tepelini?13 Oh, yes; it was in his service that my father made his fortune.”

“True, I had forgotten that.”

“Well, what is Haydée to Ali Tepelini?”

“Merely his daughter.”

“What? the daughter of Ali Pasha?”

“Of Ali Pasha and the beautiful Vasiliki.”

“And your slave?”

“Ma foi, yes.”

“But how did she become so?”

“Why, simply from the circumstance of my having bought her one day, as I was passing through the market at Constantinople.”

“Wonderful! Really, my dear count, you seem to throw a sort of magic influence over all in which you are concerned; when I listen to you, existence no longer seems reality, but a waking dream. Now, I am perhaps going to make an imprudent and thoughtless request, but——”

“Say on.”

“But, since you go out with Haydée, and sometimes even take her to the Opera——”

“Well?”

“I think I may venture to ask you this favor.”

“You may venture to ask me anything.”

“Well then, my dear count, present me to your princess.”

“I will do so; but on two conditions.”

“I accept them at once.”

“The first is, that you will never tell anyone that I have granted the interview.”

“Very well,” said Albert, extending his hand; “I swear I will not.”

“The second is, that you will not tell her that your father ever served hers.”

“I give you my oath that I will not.”

“Enough, viscount; you will remember those two vows, will you not? But I know you to be a man of honor.”

The count again struck the gong. Ali reappeared. “Tell Haydée,” said he, “that I will take coffee with her, and give her to understand that I desire permission to present one of my friends to her.”

Ali bowed and left the room.

“Now, understand me,” said the count, “no direct questions, my dear Morcerf; if you wish to know anything, tell me, and I will ask her.”

“Agreed.”

Ali reappeared for the third time, and drew back the tapestried hanging which concealed the door, to signify to his master and Albert that they were at liberty to pass on.

“Let us go in,” said Monte Cristo.

Albert passed his hand through his hair, and curled his moustache, then, having satisfied himself as to his personal appearance, followed the count into the room, the latter having previously resumed his hat and gloves. Ali was stationed as a kind of advanced guard, and the door was kept by the three French attendants, commanded by Myrtho.

Haydée was awaiting her visitors in the first room of her apartments, which was the drawing-room. Her large eyes were dilated with surprise and expectation, for it was the first time that any man, except Monte Cristo, had been accorded an entrance into her presence. She was sitting on a sofa placed in an angle of the room, with her legs crossed under her in the Eastern fashion, and seemed to have made for herself, as it were, a kind of nest in the rich Indian silks which enveloped her. Near her was the instrument on which she had just been playing; it was elegantly fashioned, and worthy of its mistress. On perceiving Monte Cristo, she arose and welcomed him with a smile peculiar to herself, expressive at once of the most implicit obedience and also of the deepest love. Monte Cristo advanced towards her and extended his hand, which she as usual raised to her lips.

Albert had proceeded no farther than the door, where he remained rooted to the spot, being completely fascinated by the sight of such surpassing beauty, beheld as it was for the first time, and of which an inhabitant of more northern climes could form no adequate idea.

“Whom do you bring?” asked the young girl in Romaic, of Monte Cristo; “is it a friend, a brother, a simple acquaintance, or an enemy.”

“A friend,” said Monte Cristo in the same language.

“What is his name?”

“Count Albert; it is the same man whom I rescued from the hands of the banditti at Rome.”

“In what language would you like me to converse with him?”

Monte Cristo turned to Albert. “Do you know modern Greek,” asked he.

“Alas! no,” said Albert; “nor even ancient Greek, my dear count; never had Homer or Plato a more unworthy scholar than myself.”

“Then,” said Haydée, proving by her remark that she had quite understood Monte Cristo’s question and Albert’s answer, “then I will speak either in French or Italian, if my lord so wills it.”

Monte Cristo reflected one instant. “You will speak in Italian,” said he.

Then, turning towards Albert,—“It is a pity you do not understand either ancient or modern Greek, both of which Haydée speaks so fluently; the poor child will be obliged to talk to you in Italian, which will give you but a very false idea of her powers of conversation.”

The count made a sign to Haydée to address his visitor. “Sir,” she said to Morcerf, “you are most welcome as the friend of my lord and master.” This was said in excellent Tuscan, and with that soft Roman accent which makes the language of Dante as sonorous as that of Homer. Then, turning to Ali, she directed him to bring coffee and pipes, and when he had left the room to execute the orders of his young mistress she beckoned Albert to approach nearer to her. Monte Cristo and Morcerf drew their seats towards a small table, on which were arranged music, drawings, and vases of flowers. Ali then entered bringing coffee and chibouques; as to M. Baptistin, this portion of the building was interdicted to him. Albert refused the pipe which the Nubian offered him.

“Oh, take it—take it,” said the count; “Haydée is almost as civilized as a Parisian; the smell of a Havana is disagreeable to her, but the tobacco of the East is a most delicious perfume, you know.”

Ali left the room. The cups of coffee were all prepared, with the addition of sugar, which had been brought for Albert. Monte Cristo and Haydée took the beverage in the original Arabian manner, that is to say, without sugar. Haydée took the porcelain cup in her little slender fingers and conveyed it to her mouth with all the innocent artlessness of a child when eating or drinking something which it likes. At this moment two women entered, bringing salvers filled with ices and sherbet, which they placed on two small tables appropriated to that purpose.

“My dear host, and you, signora,” said Albert, in Italian, “excuse my apparent stupidity. I am quite bewildered, and it is natural that it should be so. Here I am in the heart of Paris; but a moment ago I heard the rumbling of the omnibuses and the tinkling of the bells of the lemonade-sellers, and now I feel as if I were suddenly transported to the East; not such as I have seen it, but such as my dreams have painted it. Oh, signora, if I could but speak Greek, your conversation, added to the fairy-scene which surrounds me, would furnish an evening of such delight as it would be impossible for me ever to forget.”

“I speak sufficient Italian to enable me to converse with you, sir,” said Haydée quietly; “and if you like what is Eastern, I will do my best to secure the gratification of your tastes while you are here.”

“On what subject shall I converse with her?” said Albert, in a low tone to Monte Cristo.

“Just what you please; you may speak of her country and of her youthful reminiscences, or if you like it better you can talk of Rome, Naples, or Florence.”

“Oh,” said Albert, “it is of no use to be in the company of a Greek if one converses just in the same style as with a Parisian; let me speak to her of the East.”

“Do so then, for of all themes which you could choose that will be the most agreeable to her taste.”

Albert turned towards Haydée. “At what age did you leave Greece, signora?” asked he.

“I left it when I was but five years old,” replied Haydée.

“And have you any recollection of your country?”

“When I shut my eyes and think, I seem to see it all again. The mind can see as well as the body. The body forgets sometimes; but the mind always remembers.”

“And how far back into the past do your recollections extend?”

“I could scarcely walk when my mother, who was called Vasiliki, which means royal,” said the young girl, tossing her head proudly, “took me by the hand, and after putting in our purse all the money we possessed, we went out, both covered with veils, to solicit alms for the prisoners, saying, ‘He who giveth to the poor lendeth to the Lord.’ Then when our purse was full we returned to the palace, and without saying a word to my father, we sent it to the convent, where it was divided amongst the prisoners.”

“And how old were you at that time?”

“I was three years old,” said Haydée.

“Then you remember everything that went on about you from the time when you were three years old?” said Albert.

“Everything.”

“Count,” said Albert, in a low tone to Monte Cristo, “do allow the signora to tell me something of her history. You prohibited my mentioning my father’s name to her, but perhaps she will allude to him of her own accord in the course of the recital, and you have no idea how delighted I should be to hear our name pronounced by such beautiful lips.”

Monte Cristo turned to Haydée, and with an expression of countenance which commanded her to pay the most implicit attention to his words, he said in Greek, “Πατρὸς μὲν ἄτην μήζε τὸ ὄνομα προδότου καὶ προδοσίαν εἰπὲ ἡμῖν,”—that is, “Tell us the fate of your father; but neither the name of the traitor nor the treason.” Haydée sighed deeply, and a shade of sadness clouded her beautiful brow.

“What are you saying to her?” said Morcerf in an undertone.