A plant I am, that scarcely grown,

Was torn from out its Eastern bed,

Where all around perfume is shed,

And life but as a dream is known;

The land that I can call my own,

By me forgotten ne’er to be,

Where trilling birds their song taught me,

And cascades with their ceaseless roar,

And all along the spreading shore

The murmurs of the sounding sea.

While yet in childhood’s happy day,

I learned upon its sun to smile,

And in my breast there seemed the while

Seething volcanic fires to play;

A bard I was, and my wish always

To call upon the fleeting wind,

With all the force of verse and mind:

“Go forth, and spread around its fame,

From zone to zone with glad acclaim,

And earth to heaven together bind!”

From “Mi Piden Versos” (1882),

verses from Madrid for his mother.

“In the Philippine Islands the American government has tried, and is trying, to carry out exactly what the greatest genius and most revered patriot ever known in the Philippines, José Rizal, steadfastly advocated.”

—From a public address at Fargo, N.D., on April 7th. 1903, by the President of the United States.

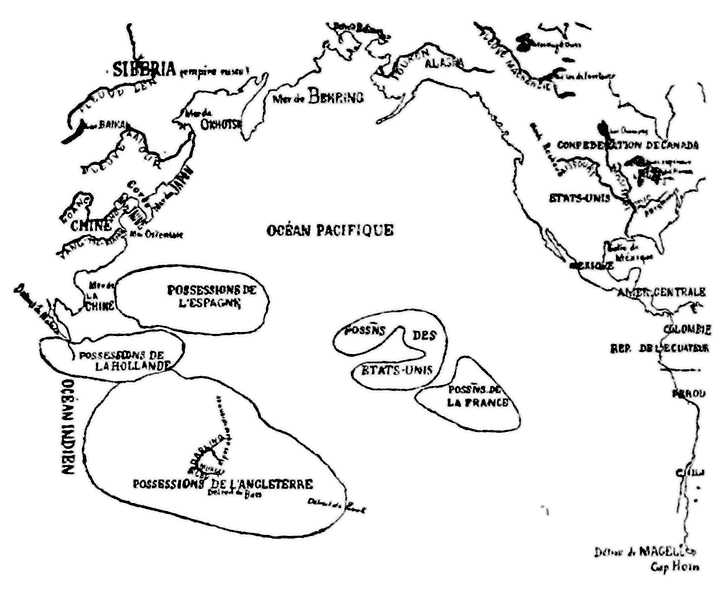

A sketch map, by Dr. Rizal, of spheres of influence in the Pacific at the time of writing “The Philippines A Century Hence,” as they appeared to him.

Most of the French names will be easily recognized, though it may be noted that “Etats Unis” is our own United States, “L’Angleterre” England, and “L’Espagne” Spain.

Introduction

As “Filipinas dentro de Cien Años”, this article was originally published serially in the Filipino fortnightly review “La Solidaridad”, of Madrid, running through the issues from September, 1889, to January, 1890.

It supplements Rizal’s great novel “Noli Me Tangere” and its sequel “El Filibusterismo”, and the translation here given is fortunately by Mr. Charles Derbyshire who in his “The Social Cancer” and “The Reign of Greed” has so happily rendered into English those masterpieces of Rizal.

The reference which Doctor Rizal makes to President Harrison had in mind the grandson-of-his-grandfather’s blundering, wavering policy that, because of a groundless fear of infringing the natives’ natural rights, put his country in the false light of wanting to share in Samoa’s exploitation, taking the leonine portion, too, along with Germany and England.

Robert Louis Stevenson has told the story of the unhappy condition created by that disastrous international agreement which was achieved by the dissembling diplomats of greedy Europe flattering unsophisticated America into believing that two monarchies preponderating in an alliance with a republic would be fairer than the republic acting unhampered.

In its day the scheme was acclaimed by irrational idealists as a triumph of American abnegation and an example of modern altruism. It resulted that “the international agreement” became a constant cause of international disagreements, as any student of history could have foretold, until, disgusted and disillusioned, the United States tardily recalled Washington’s warning against entanglements with foreign powers and became a party to a real partition, but this time playing the lamb’s part. England was compensated with concessions in other parts of the world, the United States was “given” what it already held under a cession twenty-seven years old,—and Germany took the rest as her emperor had planned from the start.

There is this Philippine bearing to the incident that the same stripe of unpractical philanthropists, not discouraged at having forced the Samoans under the ungentle German rule—for their victims and not themselves suffer by their mistakes, are seeking now the neutralization by international agreement of the Archipelago for which Rizal gave his life. Their success would mean another “entangling alliance” for the United States, with six allies, or nine including Holland, China and Spain, if the “great republic” should be allowed by the diplomats of the “Great Powers” to invite these nonentities in world politics, with whom she would still be outvoted.

Rizal’s reference to America as a possible factor in the Philippines’ future is based upon the prediction of the German traveller Feodor Jagor, who about 1860 spent a number of months in the Islands and later published his observations, supplemented by ten years of further study in European libraries and museums, as “Travels in the Philippines”, to use the title of the English translation,—a very poor one, by the way. Rizal read the much better Spanish version while a student in the Ateneo de Manila, from a copy supplied by Paciano Rizal Mercado who directed his younger brother’s political education and transferred to José the hopes which had been blighted for himself by the execution of his beloved teacher, Father Burgos, in the Cavite alleged insurrection.

Jagor’s prophecy furnishes the explanation to Rizal’s public life. His policy of preparing his countrymen for industrial and commercial competition seems to have had its inspiration in this reading done when he was a youth in years but mature in fact through close contact with tragic public events as well as with sensational private sorrows.

When in Berlin, Doctor Rizal met Professor Jagor, and the distinguished geographer and his youthful but brilliant admirer became fast friends, often discussing how the progress of events was bringing true the fortune for the Philippines which the knowledge of its history and the acquaintance with its then condition had enabled the trained observer to foretell with that same certainty that the meteorologist foretells the morrow’s weather.

A like political acumen Rizal tried to develop in his countrymen. He republished Morga’s History (first published in Mexico in 1609) to recall their past. Noli Me Tangere painted their present, and in El Filibusterismo was sketched the future which continuance upon their then course must bring. “The Philippines A Century Hence” suggests other possibilities, and seems to have been the initial issue in the series of ten which Rizal planned to print, one a year, to correct the misunderstanding of his previous writings which had come from their being known mainly by the extracts cited in the censors’ criticism.

José Rizal in life voiced the aspirations of his countrymen and as the different elements in his divided native land recognized that these were the essentials upon which all were agreed and that their points of difference among themselves were not vital, dissension disappeared and there came an united Philippines. Now, since his death, the fact that both continental and insular Americans look to him as their hero makes possible the hope that misunderstandings based on differences as to details may cease when Filipinos recognize that the American Government in the Philippines, properly approached, is willing to grant all that Rizal considered important, and when Americans understand that the people of the Philippines, unaccustomed to the frank discussions of democracy, would be content with so little even as Rizal asked of Spain if only there were some salve for their unwittingly wounded amor propio.

A better knowledge of the writings of José Rizal may accomplish this desirable consummation.

“I do not write for this generation. I am writing for other ages. If this could read me, they would burn my books, the work of my whole life. On the other hand, the generation which interprets these writings will be an educated generation; they will understand me and say: ‘Not all were asleep in the night-time of our grandparents’.”

—The Philosopher Tasio, in Noli Me Tangere.

Jagor’s Prophecy

The Prophecy Which Prompted Rizal’s Policy of Preparation For the Philippines

This extract is translated from Pages 287–289 of “Reisen in den Philippinen von F. Jagor: Berlin 1873”.

“The old situation is no longer possible of maintenance, with the changed conditions of the present time.

“The colony can no longer be kept secluded from the world. Every facility afforded for commercial intercourse is a blow to the old system, and a great step made in the direction of broad and liberal reforms. The more foreign capital and foreign ideas and customs are introduced, increasing the prosperity, enlightenment, and self respect of the population, the more impatiently will the existing evils be endured.

“England can and does open her possessions unconcernedly to the world. The British colonies are united to the mother country by the bond of mutual advantage, viz., the production of raw material by means of English capital, and the exchange of the same for English manufactures. The wealth of England is so great, the organization of her commerce with the world so complete, that nearly all the foreigners even in the British possessions are for the most part agents for English business houses, which would scarcely be affected, at least to any marked extent, by a political dismemberment. It is entirely different with Spain, which possesses the colony as an inherited property, and without the power of turning it to any useful account.

“Government monopolies rigorously maintained, insolent disregard and neglect of the half-castes and powerful creoles, and the example of the United States, were the chief reasons of the downfall of the American possessions. The same causes threaten ruin to the Philippines; but of the monopolies I have said enough.

“Half-castes and creoles, it is true, are not, as they formerly were in America, excluded from all official appointments; but they feel deeply hurt and injured through the crowds of place-hunters which the frequent changes of Ministers send to Manila.

“Also the influence of American elements is at least discernible on the horizon, and will come more to the front as the relations of the two countries grow closer. At present these are still of little importance; in the meantime commerce follows its old routes, which lead to England and the Atlantic ports of the Union. Nevertheless, he who attempts to form a judgment as to the future destiny of the Philippines cannot fix his gaze only on their relations to Spain; he must also consider the mighty changes which within a few decades are being effected on that side of our planet. For the first time in the world’s history, the gigantic nations on both sides of a gigantic ocean are beginning to come into direct intercourse: Russia, which alone is greater than two divisions of the world together; China, which within her narrow bounds contains a third of the human race; America, with cultivable soil enough to support almost three times the entire population of the earth. Russia’s future rôle in the Pacific Ocean at present baffles all calculations. The intercourse of the two other powers will probably have all the more important consequences when the adjustment between the immeasurable necessity for human labor-power on the one hand, and a correspondingly great surplus of that power on the other, shall fall on it as a problem.”

“The world of the ancients was confined to the shores of the Mediterranean; and the Atlantic and Indian Oceans sufficed at one time for our traffic. When first the shores of the Pacific re-echoed with the sounds of active commerce, the trade of the world and the history of the world may be really said to have begun. A start in that direction has been made; whereas not so very long ago the immense ocean was one wide waste of waters, traversed from both points only once a year. From 1603 to 1769 scarcely a ship had ever visited California, that wonderful country which, twenty-five years ago, with the exception of a few places on the coast, was an unknown wilderness, but which is now covered with flourishing and prosperous towns and cities, divided from sea to sea by a railway, and its capital already ranking among the world’s greatest seaports.

“But in proportion as the commerce of the western coast of America extends the influence of the American elements over the South Sea, the ensnaring spell which the great republic exercises over the Spanish colonies will not fail to assert itself in the Philippines also. The Americans appear to be called upon to bring the germ planted by the Spaniards to its full development. As conquerors of the New World, representatives of the body of free citizens in contradistinction to the nobility, they follow with the axe and plow of the pioneer where the Spaniards had opened the way with cross and sword. A considerable part of Spanish America already belongs to the United States, and has, since that occurred, attained an importance which could not have been anticipated either during Spanish rule or during the anarchy which ensued after and from it. In the long run, the Spanish system cannot prevail over the American. While the former exhausts the colonies through direct appropriation of them to the privileged classes, and the metropolis through the drain of its best forces (with, besides, a feeble population), America draws to itself the most energetic element from all lands; and these on her soil, free from all trammels, and restlessly pushing forward, are continually extending further her power and influence. The Philippines will so much the less escape the influence of the two great neighboring empires, since neither the islands nor their metropolis are in a condition of stable equilibrium. It seems desirable for the natives that the opinions here expressed shall not too soon be realized as facts, for their training thus far has not sufficiently prepared them for success in the contest with those restless, active, most inconsiderate peoples; they have dreamed away their youth.”

I.

Following our usual custom of facing squarely the most difficult and delicate questions relating to the Philippines, without weighing the consequences that our frankness may bring upon us, we shall in the present article treat of their future.

In order to read the destiny of a people, it is necessary to open the book of its past, and this, for the Philippines, may be reduced in general terms to what follows.

Scarcely had they been attached to the Spanish crown than they had to sustain with their blood and the efforts of their sons the wars and ambitions of conquest of the Spanish people, and in these struggles, in that terrible crisis when a people changes its form of government, its laws, usages, customs, religion and beliefs the Philippines were depopulated, impoverished and retarded—caught in their metamorphosis, without confidence in their past, without faith in their present and with no fond hope for the years to come. The former rulers who had merely endeavored to secure the fear and submission of their subjects, habituated by them to servitude, fell like leaves from a dead tree, and the people, who had no love for them nor knew what liberty was, easily changed masters, perhaps hoping to gain something by the innovation.

Then began a new era for the Filipinos. They gradually lost their ancient traditions, their recollections—they forgot their writings, their songs, their poetry, their laws, in order to learn by heart other doctrines, which they did not understand, other ethics, other tastes, different from those inspired in their race by their climate and their way of thinking. Then there was a falling-off, they were lowered in their own eyes, they became ashamed of what was distinctively their own, in order to admire and praise what was foreign and incomprehensible: their spirit was broken and they acquiesced.

Thus years and centuries rolled on. Religious shows, rites that caught the eye, songs, lights, images arrayed with gold, worship in a strange language, legends, miracles and sermons, hypnotized the already naturally superstitious spirit of the country, but did not succeed in destroying it altogether, in spite of the whole system afterwards developed and operated with unyielding tenacity.

When the ethical abasement of the inhabitants had reached this stage, when they had become disheartened and disgusted with themselves, an effort was made to add the final stroke for reducing so many dormant wills and intellects to nothingness, in order to make of the individual a sort of toiler, a brute, a beast of burden, and to develop a race without mind or heart. Then the end sought was revealed, it was taken for granted, the race was insulted, an effort was made to deny it every virtue, every human characteristic, and there were even writers and priests who pushed the movement still further by trying to deny to the natives of the country not only capacity for virtue but also even the tendency to vice.

Then this which they had thought would be death was sure salvation. Some dying persons are restored to health by a heroic remedy.

So great endurance reached its climax with the insults, and the lethargic spirit woke to life. His sensitiveness, the chief trait of the native, was touched, and while he had had the forbearance to suffer and die under a foreign flag, he had it not when they whom he served repaid his sacrifices with insults and jests. Then he began to study himself and to realize his misfortune. Those who had not expected this result, like all despotic masters, regarded as a wrong every complaint, every protest, and punished it with death, endeavoring thus to stifle every cry of sorrow with blood, and they made mistake after mistake.

The spirit of the people was not thereby cowed, and even though it had been awakened in only a few hearts, its flame nevertheless was surely and consumingly propagated, thanks to abuses and the stupid endeavors of certain classes to stifle noble and generous sentiments. Thus when a flame catches a garment, fear and confusion propagate it more and more, and each shake, each blow, is a blast from the bellows to fan it into life.

Undoubtedly during all this time there were not lacking generous and noble spirits among the dominant race that tried to struggle for the rights of humanity and justice, or sordid and cowardly ones among the dominated that aided the debasement of their own country. But both were exceptions and we are speaking in general terms.

Such is an outline of their past. We know their present. Now, what will their future be?

Will the Philippine Islands continue to be a Spanish colony, and if so, what kind of colony? Will they become a province of Spain, with or without autonomy? And to reach this stage, what kind of sacrifices will have to be made?

Will they be separated from the mother country to live independently, to fall into the hands of other nations, or to ally themselves with neighboring powers?

It is impossible to reply to these questions, for to all of them both yes and no may be answered, according to the time desired to be covered. When there is in nature no fixed condition, how much less must there be in the life of a people, beings endowed with mobility and movement! So it is that in order to deal with these questions, it is necessary to presume an unlimited period of time, and in accordance therewith try to forecast future events.

II.

What will become of the Philippines within a century? Will they continue to be a Spanish colony?

Had this question been asked three centuries ago, when at Legazpi’s death the Malayan Filipinos began to be gradually undeceived and, finding the yoke heavy, tried in vain to shake it off, without any doubt whatsoever the reply would have been easy. To a spirit enthusiastic over the liberty of the country, to those unconquerable Kagayanes who nourished within themselves the spirit of the Magalats, to the descendants of the heroic Gat Pulintang and Gat Salakab of the Province of Batangas, independence was assured, it was merely a question of getting together and making a determined effort. But for him who, disillusioned by sad experience, saw everywhere discord and disorder, apathy and brutalization in the lower classes, discouragement and disunion in the upper, only one answer presented itself, and it was: extend his hands to the chains, bow his neck beneath the yoke and accept the future with the resignation of an invalid who watches the leaves fall and foresees a long winter amid whose snows he discerns the outlines of his grave. At that time discord justified pessimism—but three centuries passed, the neck had become accustomed to the yoke, and each new generation, begotten in chains, was constantly better adapted to the new order of things.

Now, then, are the Philippines in the same condition they were three centuries ago?

For the liberal Spaniards the ethical condition of the people remains the same, that is, the native Filipinos have not advanced; for the friars and their followers the people have been redeemed from savagery, that is, they have progressed; for many Filipinos ethics, spirit and customs have decayed, as decay all the good qualities of a people that falls into slavery that is, they have retrograded.

Laying aside these considerations, so as not to get away from our subject, let us draw a brief parallel between the political situation then and the situation at present, in order to see if what was not possible at that time can be so now, or vice versa.

Let us pass over the loyalty the Filipinos may feel for Spain; let us suppose for a moment, along with Spanish writers, that there exist only motives for hatred and jealousy between the two races; let us admit the assertions flaunted by many that three centuries of domination have not awakened in the sensitive heart of the native a single spark of affection or gratitude; and we may see whether or not the Spanish cause has gained ground in the Islands.

Formerly the Spanish authority was upheld among the natives by a handful of soldiers, three to five hundred at most, many of whom were engaged in trade and were scattered about not only in the Islands but also among the neighboring nations, occupied in long wars against the Mohammedans in the south, against the British and Dutch, and ceaselessly harassed by Japanese, Chinese, or some tribe in the interior. Then communication with Mexico and Spain was slow, rare and difficult; frequent and violent the disturbances among the ruling powers in the Islands, the treasury nearly always empty, and the life of the colonists dependent upon one frail ship that handled the Chinese trade. Then the seas in those regions were infested with pirates, all enemies of the Spanish name, which was defended by an improvised fleet, generally manned by rude adventurers, when not by foreigners and enemies, as happened in the expedition of Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas, which was checked and frustrated by the mutiny of the Chinese rowers, who killed him and thwarted all his plans and schemes. Yet in spite of so many adverse circumstances the Spanish authority has been upheld for more than three centuries and, though it has been curtailed, still continues to rule the destinies of the Philippine group.

On the other hand, the present situation seems to be gilded and rosy—as we might say, a beautiful morning compared to the vexed and stormy night of the past. The material forces at the disposal of the Spanish sovereign have now been trebled; the fleet relatively improved; there is more organization in both civil and military affairs; communication with the sovereign country is swifter and surer; she has no enemies abroad; her possession is assured; and the country dominated seems to have less spirit, less aspiration for independence, a word that is to it almost incomprehensible. Everything then at first glance presages another three centuries, at least, of peaceful domination and tranquil suzerainty.

But above the material considerations are arising others, invisible, of an ethical nature, far more powerful and transcendental.

Orientals, and the Malays in particular, are a sensitive people: delicacy of sentiment is predominant with them. Even now, in spite of contact with the occidental nations, who have ideals different from his, we see the Malayan Filipino sacrifice everything—liberty, ease, welfare, name, for the sake of an aspiration or a conceit, sometimes scientific, or of some other nature, but at the least word which wounds his self-love he forgets all his sacrifices, the labor expended, to treasure in his memory and never forget the slight he thinks he has received.

So the Philippine peoples have remained faithful during three centuries, giving up their liberty and their independence, sometimes dazzled by the hope of the Paradise promised, sometimes cajoled by the friendship offered them by a noble and generous people like the Spanish, sometimes also compelled by superiority of arms of which they were ignorant and which timid spirits invested with a mysterious character, or sometimes because the invading foreigner took advantage of intestine feuds to step in as the peacemaker in discord and thus later to dominate both parties and subject them to his authority.

Spanish domination once established, it was firmly maintained, thanks to the attachment of the people, to their mutual dissensions, and to the fact that the sensitive self-love of the native had not yet been wounded. Then the people saw their own countrymen in the higher ranks of the army, their general officers fighting beside the heroes of Spain and sharing their laurels, begrudged neither character, reputation nor consideration; then fidelity and attachment to Spain, love of the fatherland, made of the native, encomendero1 and even general, as during the English invasion; then there had not yet been invented the insulting and ridiculous epithets with which recently the most laborious and painful achievements of the native leaders have been stigmatized; not then had it become the fashion to insult and slander in stereotyped phrase, in newspapers and books published with governmental and superior ecclesiastical approval, the people that paid, fought and poured out its blood for the Spanish name, nor was it considered either noble or witty to offend a whole race, which was forbidden to reply or defend itself; and if there were religious hypochondriacs who in the leisure of their cloisters dared to write against it, as did the Augustinian Gaspar de San Agustin and the Jesuit Velarde, their loathsome abortions never saw the light, and still less were they themselves rewarded with miters and raised to high offices. True it is that neither were the natives of that time such as we are now: three centuries of brutalization and obscurantism have necessarily had some influence upon us, the most beautiful work of divinity in the hands of certain artisans may finally be converted into a caricature.

The priests of that epoch, wishing to establish their domination over the people, got in touch with it and made common cause with it against the oppressive encomenderos. Naturally, the people saw in them greater learning and some prestige and placed its confidence in them, followed their advice, and listened to them even in the darkest hours. If they wrote, they did so in defense of the rights of the native and made his cry reach even to the distant steps of the Throne. And not a few priests, both secular and regular, undertook dangerous journeys, as representatives of the country, and this, along with the strict and public residencia2 then required of the governing powers, from the captain-general to the most insignificant official, rather consoled and pacified the wounded spirits, satisfying, even though it were only in form, all the malcontents.

All this has passed away. The derisive laughter penetrates like mortal poison into the heart of the native who pays and suffers and it becomes more offensive the more immunity it enjoys. A common sore, the general affront offered to a whole race, has wiped away the old feuds among different provinces. The people no longer has confidence in its former protectors, now its exploiters and executioners. The masks have fallen. It has seen that the love and piety of the past have come to resemble the devotion of a nurse who, unable to live elsewhere, desires eternal infancy, eternal weakness, for the child in order to go on drawing her wages and existing at its expense; it has seen not only that she does not nourish it to make it grow but that she poisons it to stunt its growth, and at the slightest protest she flies into a rage! The ancient show of justice, the holy residencia, has disappeared; confusion of ideas begins to prevail; the regard shown for a governor-general, like La Torre, becomes a crime in the government of his successor, sufficient to cause the citizen to lose his liberty and his home; if he obey the order of one official, as in the recent matter of admitting corpses into the church, it is enough to have the obedient subject later harassed and persecuted in every possible way; obligations and taxes increase without thereby increasing rights, privileges and liberties or assuring the few in existence; a régime of continual terror and uncertainty disturbs the minds, a régime worse than a period of disorder, for the fears that the imagination conjures up are generally greater than the reality; the country is poor; the financial crisis through which it is passing is acute, and every one points out with the finger the persons who are causing the trouble, yet no one dares lay hands upon them!

True it is that the Penal Code has come like a drop of balm to such bitterness.3 But of what use are all the codes in the world, if by means of confidential reports, if for trifling reasons, if through anonymous traitors any honest citizen may be exiled or banished without a hearing, without a trial? Of what use is that Penal Code, of what use is life, if there is no security in the home, no faith in justice and confidence in tranquility of conscience? Of what use is all that array of terms, all that collection of articles, when the cowardly accusation of a traitor has more influence in the timorous ears of the supreme autocrat than all the cries for justice?

If this state of affairs should continue, what will become of the Philippines within a century?

The batteries are gradually becoming charged and if the prudence of the government does not provide an outlet for the currents that are accumulating, some day the spark will be generated. This is not the place to speak of what outcome such a deplorable conflict might have, for it depends upon chance, upon the weapons and upon a thousand circumstances which man can not foresee. But even though all the advantage should be on the government’s side and therefore the probability of success, it would be a Pyrrhic victory, and no government ought to desire such.

If those who guide the destinies of the Philippines remain obstinate, and instead of introducing reforms try to make the condition of the country retrograde, to push their severity and repression to extremes against the classes that suffer and think, they are going to force the latter to venture and put into play the wretchedness of an unquiet life, filled with privation and bitterness, against the hope of securing something indefinite. What would be lost in the struggle? Almost nothing: the life of the numerous discontented classes has no such great attraction that it should be preferred to a glorious death. It may indeed be a suicidal attempt—but then, what? Would not a bloody chasm yawn between victors and vanquished, and might not the latter with time and experience become equal in strength, since they are superior in numbers, to their dominators? Who disputes this? All the petty insurrections that have occurred in the Philippines were the work of a few fanatics or discontented soldiers, who had to deceive and humbug the people or avail themselves of their power over their subordinates to gain their ends. So they all failed. No insurrection had a popular character or was based on a need of the whole race or fought for human rights or justice, so it left no ineffaceable impressions, but rather when they saw that they had been duped the people bound up their wounds and applauded the overthrow of the disturbers of their peace! But what if the movement springs from the people themselves and bases its cause upon their woes?

So then, if the prudence and wise reforms of our ministers do not find capable and determined interpreters among the colonial governors and faithful perpetuators among those whom the frequent political changes send to fill such a delicate post; if met with the eternal it is out of order, proffered by the elements who see their livelihood in the backwardness of their subjects; if just claims are to go unheeded, as being of a subversive tendency; if the country is denied representation in the Cortes and an authorized voice to cry out against all kinds of abuses, which escape through the complexity of the laws; if, in short, the system, prolific in results of alienating the good will of the natives, is to continue, pricking his apathetic mind with insults and charges of ingratitude, we can assert that in a few years the present state of affairs will have been modified completely—and inevitably. There now exists a factor which was formerly lacking—the spirit of the nation has been aroused, and a common misfortune, a common debasement, has united all the inhabitants of the Islands. A numerous enlightened class now exists within and without the Islands, a class created and continually augmented by the stupidity of certain governing powers, which forces the inhabitants to leave the country, to secure education abroad, and it is maintained and struggles thanks to the provocations and the system of espionage in vogue. This class, whose number is cumulatively increasing, is in constant communication with the rest of the Islands, and if today it constitutes only the brain of the country in a few years it will form the whole nervous system and manifest its existence in all its acts.

Now, statecraft has various means at its disposal for checking a people on the road to progress: the brutalization of the masses through a caste addicted to the government, aristocratic, as in the Dutch colonies, or theocratic, as in the Philippines; the impoverishment of the country; the gradual extermination of the inhabitants; and the fostering of feuds among the races.

Brutalization of the Malayan Filipino has been demonstrated to be impossible. In spite of the dark horde of friars, in whose hands rests the instruction of youth, which miserably wastes years and years in the colleges, issuing therefrom tired, weary and disgusted with books; in spite of the censorship, which tries to close every avenue to progress; in spite of all the pulpits, confessionals, books and missals that inculcate hatred toward not only all scientific knowledge but even toward the Spanish language itself; in spite of this whole elaborate system perfected and tenaciously operated by those who wish to keep the Islands in holy ignorance, there exist writers, freethinkers, historians, philosophers, chemists, physicians, artists and jurists. Enlightenment is spreading and the persecution it suffers quickens it. No, the divine flame of thought is inextinguishable in the Filipino people and somehow or other it will shine forth and compel recognition. It is impossible to brutalize the inhabitants of the Philippines!

May poverty arrest their development?

Perhaps, but it is a very dangerous means. Experience has everywhere shown us and especially in the Philippines, that the classes which are better off have always been addicted to peace and order, because they live comparatively better and may be the losers in civil disturbances. Wealth brings with it refinement, the spirit of conservation, while poverty inspires adventurous ideas, the desire to change things, and has little care for life. Machiavelli himself held this means of subjecting a people to be perilous, observing that loss of welfare stirs up more obdurate enemies than loss of life. Moreover, when there are wealth and abundance, there is less discontent, less complaint, and the government, itself wealthier, has more means for sustaining itself. On the other hand, there occurs in a poor country what happens in a house where bread is wanting. And further, of what use to the mother country would a poor and lean colony be?

Neither is it possible gradually to exterminate the inhabitants. The Philippine races, like all the Malays, do not succumb before the foreigner, like the Australians, the Polynesians and the Indians of the New World. In spite of the numerous wars the Filipinos have had to carry on, in spite of the epidemics that have periodically visited them, their number has trebled, as has that of the Malays of Java and the Moluccas. The Filipino embraces civilization and lives and thrives in every clime, in contact with every people. Rum, that poison which exterminated the natives of the Pacific islands, has no power in the Philippines, but, rather, comparison of their present condition with that described by the early historians, makes it appear that the Filipinos have grown soberer. The petty wars with the inhabitants of the South consume only the soldiers, people who by their fidelity to the Spanish flag, far from being a menace, are surely one of its solidest supports.

There remains the fostering of intestine feuds among the provinces.

This was formerly possible, when communication from one island to another was rare and difficult, when there were no steamers or telegraph-lines, when the regiments were formed according to the various provinces, when some provinces were cajoled by awards of privileges and honors and others were protected from the strongest. But now that the privileges have disappeared, that through a spirit of distrust the regiments have been reorganized, that the inhabitants move from one island to another, communication and exchange of impressions naturally increase, and as all see themselves threatened by the same peril and wounded in the same feelings, they clasp hands and make common cause. It is true that the union is not yet wholly perfected, but to this end tend the measures of good government, the vexations to which the townspeople are subjected, the frequent changes of officials, the scarcity of centers of learning, which forces the youth of all the Islands to come together and begin to get acquainted. The journeys to Europe contribute not a little to tighten the bonds, for abroad the inhabitants of the most widely separated provinces are impressed by their patriotic feelings, from sailors even to the wealthiest merchants, and at the sight of modern liberty and the memory of the misfortunes of their country, they embrace and call one another brothers.

In short, then, the advancement and ethical progress of the Philippines are inevitable, are decreed by fate.

The Islands cannot remain in the condition they are without requiring from the sovereign country more liberty Mutatis mutandis. For new men, a new social order.

To wish that the alleged child remain in its swaddling-clothes is to risk that it may turn against its nurse and flee, tearing away the old rags that bind it.

The Philippines, then, will remain under Spanish domination, but with more law and greater liberty, or they will declare themselves independent, after steeping themselves and the mother country in blood.

As no one should desire or hope for such an unfortunate rupture, which would be an evil for all and only the final argument in the most desperate predicament, let us see by what forms of peaceful evolution the Islands may remain subjected to the Spanish authority with the very least detriment to the rights, interests and dignity of both parties.

III.

If the Philippines must remain under the control of Spain, they will necessarily have to be transformed in a political sense, for the course of their history and the needs of their inhabitants so require. This we demonstrated in the preceding article.

We also said that this transformation will be violent and fatal if it proceeds from the ranks of the people, but peaceful and fruitful if it emanate from the upper classes.

Some governors have realized this truth, and, impelled by their patriotism, have been trying to introduce needed reforms in order to forestall events. But notwithstanding all that have been ordered up to the present time, they have produced scanty results, for the government as well as for the country. Even those that promised only a happy issue have at times caused injury, for the simple reason that they have been based upon unstable grounds.

We said, and once more we repeat, and will ever assert, that reforms which have a palliative character are not only ineffectual but even prejudicial, when the government is confronted with evils that must be cured radically. And were we not convinced of the honesty and rectitude of some governors, we would be tempted to say that all the partial reforms are only plasters and salves of a physician who, not knowing how to cure the cancer, and not daring to root it out, tries in this way to alleviate the patient’s sufferings or to temporize with the cowardice of the timid and ignorant.

All the reforms of our liberal ministers were, have been, are, and will be good—when carried out.

When we think of them, we are reminded of the dieting of Sancho Panza in his Barataria Island. He took his seat at a sumptuous and well-appointed table “covered with fruit and many varieties of food differently prepared,” but between the wretch’s mouth and each dish the physician Pedro Rezio interposed his wand, saying, “Take it away!” The dish removed, Sancho was as hungry as ever. True it is that the despotic Pedro Rezio gave reasons, which seem to have been written by Cervantes especially for the colonial administrations: “You must not eat, Mr. Governor, except according to the usage and custom of other islands where there are governors.” Something was found to be wrong with each dish: one was too hot, another too moist, and so on, just like our Pedro Rezios on both sides of the sea. Great good did his cook’s skill do Sancho!4

In the case of our country, the reforms take the place of the dishes, the Philippines are Sancho, while the part of the quack physician is played by many persons, interested in not having the dishes touched, perhaps that they may themselves get the benefit of them.

The result is that the long-suffering Sancho, or the Philippines, misses his liberty, rejects all government and ends up by rebelling against his quack physician.

In like manner, so long as the Philippines have no liberty of the press, have no voice in the Cortes to make known to the government and to the nation whether or not their decrees have been duly obeyed, whether or not these benefit the country, all the able efforts of the colonial ministers will meet the fate of the dishes in Barataria island.

The minister, then, who wants his reforms to be reforms, must begin by declaring the press in the Philippines free and by instituting Filipino delegates.

The press is free in the Philippines, because their complaints rarely ever reach the Peninsula, very rarely, and if they do they are so secret, so mysterious, that no newspaper dares to publish them, or if it does reproduce them, it does so tardily and badly.

A government that rules a country from a great distance is the one that has the most need for a free press, more so even than the government of the home country, if it wishes to rule rightly and fitly. The government that governs in a country may even dispense with the press (if it can), because it is on the ground, because it has eyes and ears, and because it directly observes what it rules and administers. But the government that governs from afar absolutely requires that the truth and the facts reach its knowledge by every possible channel, so that it may weigh and estimate them better, and this need increases when a country like the Philippines is concerned, where the inhabitants speak and complain in a language unknown to the authorities. To govern in any other way may also be called governing, but it is to govern badly. It amounts to pronouncing judgment after hearing only one of the parties; it is steering a ship without reckoning its conditions, the state of the sea, the reefs and shoals, the direction of the winds and currents. It is managing a house by endeavoring merely to give it polish and a fine appearance without watching the money-chest, without looking after the servants and the members of the family.

But routine is a declivity down which many governments slide, and routine says that freedom of the press is dangerous. Let us see what History says: uprisings and revolutions have always occurred in countries tyrannized over, in countries where human thought and the human heart have been forced to remain silent.

If the great Napoleon had not tyrannized over the press, perhaps it would have warned him of the peril into which he was hurled and have made him understand that the people were weary and the earth wanted peace. Perhaps his genius, instead of being dissipated in foreign aggrandizement, would have become intensive in laboring to strengthen his position and thus have assured it. Spain herself records in her history more revolutions when the press was gagged. What colonies have become independent while they have had a free press and enjoyed liberty? Is it preferable to govern blindly or to govern with ample knowledge?

Some one will answer that in colonies with a free press, the prestige of the rulers, that prop of false governments, will be greatly imperiled. We answer that the prestige of the nation is preferable to that of a few individuals. A nation acquires respect, not by abetting and concealing abuses, but by rebuking and punishing them. Moreover, to this prestige is applicable what Napoleon said about great men and their valets. We, who endure and know all the false pretensions and petty persecutions of those sham gods, do not need a free press in order to recognize them; they have long ago lost their prestige. The free press is needed by the government, the government which still dreams of the prestige which it builds upon mined ground.

We say the same about the Filipino representatives.

What risks does the government see in them? One of three things: either that they will prove unruly, become political trimmers, or act properly.

Supposing that we should yield to the most absurd pessimism and admit the insult, great for the Philippines, but still greater for Spain, that all the representatives would be separatists and that in all their contentions they would advocate separatist ideas: does not a patriotic Spanish majority exist there, is there not present there the vigilance of the governing powers to combat and oppose such intentions? And would not this be better than the discontent that ferments and expands in the secrecy of the home, in the huts and in the fields? Certainly the Spanish people does not spare its blood where patriotism is concerned, but would not a struggle of principles in parliament be preferable to the exchange of shot in swampy lands, three thousand leagues from home, in impenetrable forests, under a burning sun or amid torrential rains? These pacific struggles of ideas, besides being a thermometer for the government, have the advantage of being cheap and glorious, because the Spanish parliament especially abounds in oratorical paladins, invincible in debate. Moreover, it is said that the Filipinos are indolent and peaceful—then what need the government fear? Hasn’t it any influence in the elections? Frankly, it is a great compliment to the separatists to fear them in the midst of the Cortes of the nation.

If they become political trimmers, as is to be expected and as they probably will be, so much the better for the government and so much the worse for their constituents. They would be a few more favorable votes, and the government could laugh openly at the separatists, if any there be.

If they become what they should be, worthy, honest and faithful to their trust, they will undoubtedly annoy an ignorant or incapable minister with their questions, but they will help him to govern and will be some more honorable figures among the representatives of the nation.

Now then, if the real objection to the Filipino delegates is that they smell like Igorots, which so disturbed in open Senate the doughty General Salamanca, then Don Sinibaldo de Mas, who saw the Igorots in person and wanted to live with them, can affirm that they will smell at worst like powder, and Señor Salamanca undoubtedly has no fear of that odor. And if this were all, the Filipinos, who there in their own country are accustomed to bathe every day, when they become representatives may give up such a dirty custom, at least during the legislative session, so as not to offend the delicate nostrils of the Salamancas with the odor of the bath.

It is useless to answer certain objections of some fine writers regarding the rather brown skins and faces with somewhat wide nostrils. Questions of taste are peculiar to each race. China, for example, which has four hundred million inhabitants and a very ancient civilization, considers all Europeans ugly and calls them “fan-kwai,” or red devils. Its taste has a hundred million more adherents than the European. Moreover, if this is the question, we would have to admit the inferiority of the Latins, especially the Spaniards, to the Saxons, who are much whiter.

And so long as it is not asserted that the Spanish parliament is an assemblage of Adonises, Antinouses, pretty boys, and other like paragons; so long as the purpose of resorting thither is to legislate and not to philosophize or to wander through imaginary spheres, we maintain that the government ought not to pause at these objections. Law has no skin, nor reason nostrils.

So we see no serious reason why the Philippines may not have representatives. By their institution many malcontents would be silenced, and instead of blaming its troubles upon the government, as now happens, the country would bear them better, for it could at least complain and with its sons among its legislators would in a way become responsible for their actions.

We are not sure that we serve the true interests of our country by asking for representatives. We know that the lack of enlightenment, the indolence, the egotism of our fellow countrymen, and the boldness, the cunning and the powerful methods of those who wish their obscurantism, may convert reform into a harmful instrument. But we wish to be loyal to the government and we are pointing out to it the road that appears best to us so that its efforts may not come to grief, so that discontent may disappear. If after so just, as well as necessary, a measure has been introduced, the Filipino people are so stupid and weak that they are treacherous to their own interests, then let the responsibility fall upon them, let them suffer all the consequences. Every country gets the fate it deserves, and the government can say that it has done its duty.

These are the two fundamental reforms, which, properly interpreted and applied, will dissipate all clouds, assure affection toward Spain, and make all succeeding reforms fruitful. These are the reforms sine quibus non.

It is puerile to fear that independence may come through them. The free press will keep the government in touch with public opinion, and the representatives, if they are, as they ought to be, the best from among the sons of the Philippines, will be their hostages. With no cause for discontent, how then attempt to stir up the masses of the people?

Likewise inadmissible is the objection offered by some regarding the imperfect culture of the majority of the inhabitants. Aside from the fact that it is not so imperfect as is averred, there is no plausible reason why the ignorant and the defective (whether through their own or another’s fault) should be denied representation to look after them and see that they are not abused. They are the very ones who most need it. No one ceases to be a man, no one forfeits his rights to civilization merely by being more or less uncultured, and since the Filipino is regarded as a fit citizen when he is asked to pay taxes or shed his blood to defend the fatherland, why must this fitness be denied him when the question arises of granting him some right? Moreover, how is he to be held responsible for his ignorance, when it is acknowledged by all, friends and enemies, that his zeal for learning is so great that even before the coming of the Spaniards every one could read and write, and that we now see the humblest families make enormous sacrifices in order that their children may become a little enlightened, even to the extent of working as servants in order to learn Spanish? How can the country be expected to become enlightened under present conditions when we see all the decrees issued by the government in favor of education meet with Pedro Rezios who prevent execution thereof, because they have in their hands what they call education? If the Filipino, then, is sufficiently intelligent to pay taxes, he must also be able to choose and retain the one who looks after him and his interests, with the product whereof he serves the government of his nation. To reason otherwise is to reason stupidly.

When the laws and the acts of officials are kept under surveillance, the word justice may cease to be a colonial jest. The thing that makes the English most respected in their possessions is their strict and speedy justice, so that the inhabitants repose entire confidence in the judges. Justice is the foremost virtue of the civilizing races. It subdues the barbarous nations, while injustice arouses the weakest.

Offices and trusts should be awarded by competition, publishing the work and the judgment thereon, so that there may be stimulus and that discontent may not be bred. Then, if the native does not shake off his indolence he can not complain when he sees all the offices filled by Castilas.

We presume that it will not be the Spaniard who fears to enter into this contest, for thus will he be able to prove his superiority by the superiority of intelligence. Although this is not the custom in the sovereign country, it should be practiced in the colonies, for the reason that genuine prestige should be sought by means of moral qualities, because the colonizers ought to be, or at least to seem, upright, honest and intelligent, just as a man simulates virtues when he deals with strangers. The offices and trusts so earned will do away with arbitrary dismissal and develop employees and officials capable and cognizant of their duties. The offices held by natives, instead of endangering the Spanish domination, will merely serve to assure it, for what interest would they have in converting the sure and stable into the uncertain and problematical? The native is, moreover, very fond of peace and prefers an humble present to a brilliant future. Let the various Filipinos still holding office speak in this matter; they are the most unshaken conservatives.

We could add other minor reforms touching commerce, agriculture, security of the individual and of property, education, and so on, but these are points with which we shall deal in other articles. For the present we are satisfied with the outlines, and no one can say that we ask too much.

There will not be lacking critics to accuse us of Utopianism: but what is Utopia? Utopia was a country imagined by Thomas Moore, wherein existed universal suffrage, religious toleration, almost complete abolition of the death penalty, and so on. When the book was published these things were looked upon as dreams, impossibilities, that is, Utopianism. Yet civilization has left the country of Utopia far behind, the human will and conscience have worked greater miracles, have abolished slavery and the death penalty for adultery—things impossible for even Utopia itself!

The French colonies have their representatives. The question has also been raised in the English parliament of giving representation to the Crown colonies, for the others already enjoy some autonomy. The press there also is free. Only Spain, which in the sixteenth century was the model nation in civilization, lags far behind. Cuba and Porto Rico, whose inhabitants do not number a third of those of the Philippines, and who have not made such sacrifices for Spain, have numerous representatives. The Philippines in the early days had theirs, who conferred with the King and the Pope on the needs of the country. They had them in Spain’s critical moments, when she groaned under the Napoleonic yoke, and they did not take advantage of the sovereign country’s misfortune like other colonies, but tightened more firmly the bonds that united them to the nation, giving proofs of their loyalty; and they continued until many years later. What crime have the Islands committed that they are deprived of their rights?

To recapitulate: the Philippines will remain Spanish, if they enter upon the life of law and civilization, if the rights of their inhabitants are respected, if the other rights due them are granted, if the liberal policy of the government is carried out without trickery or meanness, without subterfuges or false interpretations.

Otherwise, if an attempt is made to see in the Islands a lode to be exploited, a resource to satisfy ambitions, thus to relieve the sovereign country of taxes, killing the goose that lays the golden eggs and shutting its ears to all cries of reason, then, however great may be the loyalty of the Filipinos, it will be impossible to hinder the operations of the inexorable laws of history. Colonies established to subserve the policy and the commerce of the sovereign country, all eventually become independent, said Bachelet, and before Bachelet all the Phœnecian, Carthaginian, Greek, Roman, English, Portuguese and Spanish colonies had said it.

Close indeed are the bonds that unite us to Spain. Two peoples do not live for three centuries in continual contact, sharing the same lot, shedding their blood on the same fields, holding the same beliefs, worshipping the same God, interchanging the same ideas, but that ties are formed between them stronger than those fashioned by arms or fear. Mutual sacrifices and benefits have engendered affection. Machiavelli, the great reader of the human heart, said: la natura degli huomini, é cosi obligarsi per li beneficii che essi fanno, come per quelli che essi ricevono (it is human nature to be bound as much by benefits conferred as by those received). All this, and more, is true, but it is pure sentimentality, and in the arena of politics stern necessity and interests prevail. Howsoever much the Filipinos owe Spain, they can not be required to forego their redemption, to have their liberal and enlightened sons wander about in exile from their native land, the rudest aspirations stifled in its atmosphere, the peaceful inhabitant living in constant alarm, with the fortune of the two peoples dependent upon the whim of one man. Spain can not claim, not even in the name of God himself, that six millions of people should be brutalized, exploited and oppressed, denied light and the rights inherent to a human being, and then heap upon them slights and insults. There is no claim of gratitude that can excuse, there is not enough powder in the world to justify, the offenses against the liberty of the individual, against the sanctity of the home, against the laws, against peace and honor, offenses that are committed there daily. There is no divinity that can proclaim the sacrifice of our dearest affections, the sacrifice of the family, the sacrileges and wrongs that are committed by persons who have the name of God on their lips. No one can require an impossibility of the Filipino people. The noble Spanish people, so jealous of its rights and liberties, can not bid the Filipinos renounce theirs. A people that prides itself on the glories of its past can not ask another, trained by it, to accept abjection and dishonor its own name!

We who today are struggling by the legal and peaceful means of debate so understand it, and with our gaze fixed upon our ideals, shall not cease to plead our cause, without going beyond the pale of the law, but if violence first silences us or we have the misfortune to fall (which is possible, for we are mortal), then we do not know what course will be taken by the numerous tendencies that will rush in to occupy the places that we leave vacant.

If what we desire is not realized….

In contemplating such an unfortunate eventuality, we must not turn away in horror, and so instead of closing our eyes we will face what the future may bring. For this purpose, after throwing the handful of dust due to Cerberus, let us frankly descend into the abyss and sound its terrible mysteries.

IV.

History does not record in its annals any lasting domination exercised by one people over another, of different race, of diverse usages and customs, of opposite and divergent ideals.

One of the two had to yield and succumb. Either the foreigner was driven out, as happened in the case of the Carthaginians, the Moors and the French in Spain, or else these autochthons had to give way and perish, as was the case with the inhabitants of the New World, Australia and New Zealand.

One of the longest dominations was that of the Moors in Spain, which lasted seven centuries. But, even though the conquerors lived in the country conquered, even though the Peninsula was broken up into small states, which gradually emerged like little islands in the midst of the great Saracen inundation, and in spite of the chivalrous spirit, the gallantry and the religious toleration of the califs, they were finally driven out after bloody and stubborn conflicts, which formed the Spanish nation and created the Spain of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

The existence of a foreign body within another endowed with strength and activity is contrary to all natural and ethical laws. Science teaches us that it is either assimilated, destroys the organism, is eliminated or becomes encysted.

Encystment of a conquering people is impossible, for it signifies complete isolation, absolute inertia, debility in the conquering element. Encystment thus means the tomb of the foreign invader.

Now, applying these considerations to the Philippines, we must conclude, as a deduction from all we have said, that if their population be not assimilated to the Spanish nation, if the dominators do not enter into the spirit of their inhabitants, if equable laws and free and liberal reforms do not make each forget that they belong to different races, or if both peoples be not amalgamated to constitute one mass, socially and politically homogeneous, that is, not harassed by opposing tendencies and antagonistic ideas and interests, some day the Philippines will fatally and infallibly declare themselves independent. To this law of destiny can be opposed neither Spanish patriotism, nor the love of all the Filipinos for Spain, nor the doubtful future of dismemberment and intestine strife in the Islands themselves. Necessity is the most powerful divinity the world knows, and necessity is the resultant of physical forces set in operation by ethical forces.

We have said and statistics prove that it is impossible to exterminate the Filipino people. And even were it possible, what interest would Spain have in the destruction of the inhabitants of a country she can not populate or cultivate, whose climate is to a certain extent disastrous to her? What good would the Philippines be without the Filipinos? Quite otherwise, under her colonial system and the transitory character of the Spaniards who go to the colonies, a colony is so much the more useful and productive to her as it possesses inhabitants and wealth. Moreover, in order to destroy the six million Malays, even supposing them to be in their infancy and that they have never learned to fight and defend themselves, Spain would have to sacrifice at least a fourth of her population. This we commend to the notice of the partizans of colonial exploitation.

But nothing of this kind can happen. The menace is that when the education and liberty necessary to human existence are denied by Spain to the Filipinos, then they will seek enlightenment abroad, behind the mother country’s back, or they will secure by hook or by crook some advantages in their own country, with the result that the opposition of purblind and paretic politicians will not only be futile but even prejudicial, because it will convert motives for love and gratitude into resentment and hatred.

Hatred and resentment on one side, mistrust and anger on the other, will finally result in a violent and terrible collision, especially when there exist elements interested in having disturbances, so that they may get something in the excitement, demonstrate their mighty power, foster lamentations and recriminations, or employ violent measures. It is to be expected that the government will triumph and be generally (as is the custom) severe in punishment, either to teach a stern lesson in order to vaunt its strength or even to revenge upon the vanquished the spells of excitement and terror that the danger caused it. An unavoidable concomitant of those catastrophes is the accumulation of acts of injustice committed against the innocent and peaceful inhabitants. Private reprisals, denunciations, despicable accusations, resentments, covetousness, the opportune moment for calumny, the haste and hurried procedure of the courts martial, the pretext of the integrity of the fatherland and the safety of the state, which cloaks and justifies everything, even for scrupulous minds, which unfortunately are still rare, and above all the panic-stricken timidity, the cowardice that battens upon the conquered—all these things augment the severe measures and the number of the victims. The result is that a chasm of blood is then opened between the two peoples, that the wounded and the afflicted, instead of becoming fewer, are increased, for to the families and friends of the guilty, who always think the punishment excessive and the judge unjust, must be added the families and friends of the innocent, who see no advantage in living and working submissively and peacefully. Note, too, that if severe measures are dangerous in a nation made up of a homogeneous population, the peril is increased a hundred-fold when the government is formed of a race different from the governed. In the former an injustice may still be ascribed to one man alone, to a governor actuated by personal malice, and with the death of the tyrant the victim is reconciled to the government of his nation. But in a country dominated by a foreign race, even the justest act of severity is construed as injustice and oppression, because it is ordered by a foreigner, who is unsympathetic or is an enemy of the country, and the offense hurts not only the victim but his entire race, because it is not usually regarded as personal, and so the resentment naturally spreads to the whole governing race and does not die out with the offender.

Hence the great prudence and fine tact that should be exercised by colonizing countries, and the fact that government regards the colonies in general, and our colonial office in particular, as training schools, contributes notably to the fulfillment of the great law that the colonies sooner or later declare themselves independent.

Such is the descent down which the peoples are precipitated. In proportion as they are bathed in blood and drenched in tears and gall, the colony, if it has any vitality, learns how to struggle and perfect itself in fighting, while the mother country, whose colonial life depends upon peace and the submission of the subjects, is constantly weakened, and, even though she make heroic efforts, as her number is less and she has only a fictitious existence, she finally perishes. She is like the rich voluptuary accustomed to be waited upon by a crowd of servants toiling and planting for him, and who, on the day his slaves refuse him obedience, as he does not live by his own efforts, must die.

Reprisals, wrongs and suspicions on one part and on the other the sentiment of patriotism and liberty, which is aroused in these incessant conflicts, insurrections and uprisings, operate to generalize the movement and one of the two peoples must succumb. The struggle will be brief, for it will amount to a slavery much more cruel than death for the people and to a dishonorable loss of prestige for the dominator. One of the peoples must succumb.

Spain, from the number of her inhabitants, from the condition of her army and navy, from the distance she is situated from the Islands, from her scanty knowledge of them, and from struggling against a people whose love and good will she has alienated, will necessarily have to give way, if she does not wish to risk not only her other possessions and her future in Africa, but also her very independence in Europe. All this at the cost of bloodshed and crime, after mortal conflicts, murders, conflagrations, military executions, famine and misery.

The Spaniard is gallant and patriotic, and sacrifices everything, in favorable moments, for his country’s good. He has the intrepidity of his bull. The Filipino loves his country no less, and although he is quieter, more peaceful, and with difficulty stirred up, when he is once aroused he does not hesitate and for him the struggle means death to one or the other combatant. He has all the meekness and all the tenacity and ferocity of his carabao. Climate affects bipeds in the same way that it does quadrupeds.

The terrible lessons and the hard teachings that these conflicts will have afforded the Filipinos will operate to improve and strengthen their ethical nature. The Spain of the fifteenth century was not the Spain of the eighth. With their bitter experience, instead of intestine conflicts of some islands against others, as is generally feared, they will extend mutual support, like shipwrecked persons when they reach an island after a fearful night of storm. Nor may it be said that we shall partake of the fate of the small American republics. They achieved their independence easily, and their inhabitants are animated by a different spirit from what the Filipinos are. Besides, the danger of falling again into other hands, English or German, for example, will force the Filipinos to be sensible and prudent. Absence of any great preponderance of one race over the others will free their imagination from all mad ambitions of domination, and as the tendency of countries that have been tyrannized over, when they once shake off the yoke, is to adopt the freest government, like a boy leaving school, like the beat of the pendulum, by a law of reaction the Islands will probably declare themselves a federal republic.

If the Philippines secure their independence after heroic and stubborn conflicts, they can rest assured that neither England, nor Germany, nor France, and still less Holland, will dare to take up what Spain has been unable to hold. Within a few years Africa will completely absorb the attention of the Europeans, and there is no sensible nation which, in order to secure a group of poor and hostile islands, will neglect the immense territory offered by the Dark Continent, untouched, undeveloped and almost undefended. England has enough colonies in the Orient and is not going to risk losing her balance. She is not going to sacrifice her Indian Empire for the poor Philippine Islands—if she had entertained such an intention she would not have restored Manila in 1763, but would have kept some point in the Philippines, whence she might gradually expand. Moreover, what need has John Bull the trader to exhaust himself for the Philippines, when he is already lord of the Orient, when he has there Singapore, Hongkong and Shanghai? It is probable that England will look favorably upon the independence of the Philippines, for it will open their ports to her and afford greater freedom to her commerce. Furthermore, there exist in the United Kingdom tendencies and opinions to the effect that she already has too many colonies, that they are harmful, that they greatly weaken the sovereign country.

For the same reasons Germany will not care to run any risk, and because a scattering of her forces and a war in distant countries will endanger her existence on the continent. Thus we see her attitude, as much in the Pacific as in Africa, is confined to conquering easy territory that belongs to nobody. Germany avoids any foreign complications.

France has enough to do and sees more of a future in Tongking and China, besides the fact that the French spirit does not shine in zeal for colonization. France loves glory, but the glory and laurels that grow on the battlefields of Europe. The echo from battlefields in the Far East hardly satisfies her craving for renown, for it reaches her quite faintly. She has also other obligations, both internally and on the continent.

Holland is sensible and will be content to keep the Moluccas and Java. Sumatra offers her a greater future than the Philippines, whose seas and coasts have a sinister omen for Dutch expeditions. Holland proceeds with great caution in Sumatra and Borneo, from fear of losing everything.

China will consider herself fortunate if she succeeds in keeping herself intact and is not dismembered or partitioned among the European powers that are colonizing the continent of Asia.

The same is true of Japan. On the north she has Russia, who envies and watches her; on the south England, with whom she is in accord even to her official language. She is, moreover, under such diplomatic pressure from Europe that she can not think of outside affairs until she is freed from it, which will not be an easy matter. True it is that she has an excess of population, but Korea attracts her more than the Philippines and is, also, easier to seize.

Perhaps the great American Republic, whose interests lie in the Pacific and who has no hand in the spoliation of Africa, may some day dream of foreign possession. This is not impossible, for the example is contagious, covetousness and ambition are among the strongest vices, and Harrison manifested something of this sort in the Samoan question. But the Panama Canal is not opened nor the territory of the States congested with inhabitants, and in case she should openly attempt it the European powers would not allow her to proceed, for they know very well that the appetite is sharpened by the first bites. North America would be quite a troublesome rival, if she should once get into the business. Furthermore, this is contrary to her traditions.

Very likely the Philippines will defend with inexpressible valor the liberty secured at the price of so much blood and sacrifice. With the new men that will spring from their soil and with the recollection of their past, they will perhaps strive to enter freely upon the wide road of progress, and all will labor together to strengthen their fatherland, both internally and externally, with the same enthusiasm with which a youth falls again to tilling the land of his ancestors, so long wasted and abandoned through the neglect of those who have withheld it from him. Then the mines will be made to give up their gold for relieving distress, iron for weapons, copper, lead and coal. Perhaps the country will revive the maritime and mercantile life for which the islanders are fitted by their nature, ability and instincts, and once more free, like the bird that leaves its cage, like the flower that unfolds to the air, will recover the pristine virtues that are gradually dying out and will again become addicted to peace—cheerful, happy, joyous, hospitable and daring.

These and many other things may come to pass within something like a hundred years. But the most logical prognostication, the prophecy based on the best probabilities, may err through remote and insignificant causes. An octopus that seized Mark Antony’s ship altered the face of the world; a cross on Cavalry and a just man nailed thereon changed the ethics of half the human race, and yet before Christ, how many just men wrongfully perished and how many crosses were raised on that hill! The death of the just sanctified his work and made his teaching unanswerable. A sunken road at the battle of Waterloo buried all the glories of two brilliant decades, the whole Napoleonic world, and freed Europe. Upon what chance accidents will the destiny of the Philippines depend?

Nevertheless, it is not well to trust to accident, for there is sometimes an imperceptible and incomprehensible logic in the workings of history. Fortunately, peoples as well as governments are subject to it.

Therefore, we repeat, and we will ever repeat, while there is time, that it is better to keep pace with the desires of a people than to give way before them: the former begets sympathy and love, the latter contempt and anger. Since it is necessary to grant six million Filipinos their rights, so that they may be in fact Spaniards, let the government grant these rights freely and spontaneously, without damaging reservations, without irritating mistrust. We shall never tire of repeating this while a ray of hope is left us, for we prefer this unpleasant task to the need of some day saying to the mother country: “Spain, we have spent our youth in serving thy interests in the interests of our country; we have looked to thee, we have expended the whole light of our intellects, all the fervor and enthusiasm of our hearts in working for the good of what was thine, to draw from thee a glance of love, a liberal policy that would assure us the peace of our native land and thy sway over loyal but unfortunate islands! Spain, thou hast remained deaf, and, wrapped up in thy pride, hast pursued thy fatal course and accused us of being traitors, merely because we love our country, because we tell thee the truth and hate all kinds of injustice. What dost thou wish us to tell our wretched country, when it asks about the result of our efforts? Must we say to it that, since for it we have lost everything—youth, future, hope, peace, family; since in its service we have exhausted all the resources of hope, all the disillusions of desire, it also takes the residue which we can not use, the blood from our veins and the strength left in our arms? Spain, must we some day tell Filipinas that thou hast no ear for her woes and that if she wishes to be saved she must redeem herself?”

1 An encomendero was a Spanish soldier who as a reward for faithful service was set over a district with power to collect tribute and the duty of providing the people with legal protection and religious instruction. This arrangement is memorable in early Philippine annals chiefly for the flagrant abuses that appear to have characterized it.